4. Organizing Code#

Learning Objectives

After this lesson, you should be able to:

Write functions to organize and encapsulate reusable code

Create code that only runs when a condition is satisfied

Identify when a problem requires iteration

Select appropriate iteration strategies for problems

4.1. Functions#

The main way to interact with Python is by calling functions, which was first explained back in Calling Functions. This section explains how to write your own functions.

First, a review of what functions are and some of the vocabulary associated with them:

Parameters are placeholder variables for inputs.

Arguments are the actual values assigned to the parameters in a call.

The return value is the output.

Calling a function means using a function to compute something.

The body is the code inside.

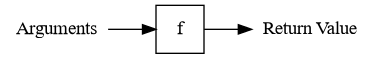

It’s useful to think of functions as factories, meaning arguments go in and a

return value comes out. Here’s a visual representation of the idea for a

function f:

A function definition begins with the def keyword, followed by:

The name of the function

A list of parameters surrounded by parentheses

A colon

:

A function can have any number of parameters. Code in the body of the function

must be indented by 4 spaces. Use the return keyword to return a result. The

return keyword causes the function to return a result immediately, without

running any subsequent code in its body.

For example, let’s create a function that detects negative numbers. It should take a series of numbers as input, compare them to zero, and then return the logical result from the comparison as output. Here’s the code to do that:

def is_negative(x):

return x < 0

The name of the function, is_negative, describes what the function does and

includes a verb. The parameter x is the input. The return value is the result

of x < 0.

Tip

Choosing descriptive names is a good habit. For functions, that means choosing a name that describes what the function does. It often makes sense to use verbs in function names.

Any time you write a function, the first thing you should do afterwards is test

that it actually works. Try the is_negative function on a few test cases:

import polars as pl

x = pl.Series([5, -1, -2, 0, 3])

is_negative(6)

False

is_negative(-1.1)

True

is_negative(x)

| bool |

| false |

| true |

| true |

| false |

| false |

Notice that the parameter x inside the function is different from the

variable x you created outside the function. Remember that parameters and

variables inside of a function are separate from variables outside of a

function.

Recall that a default argument is an argument assigned to a parameter if no

argument is assigned in the call to the function. You can use = to assign

default arguments to parameters when you define a function with the def

keyword.

For example, suppose you want to write a function that gets the largest values

in a series. You can make a parameter for the number of values to get, with a

default argument of 5. Here’s the code and some test cases:

def get_largest(x, n = 5):

return x.sort(descending=True).head(n)

y = pl.Series([-6, 7, 10, 3, 1, 15, -2])

get_largest(y, 3)

| i64 |

| 15 |

| 10 |

| 7 |

get_largest(y)

| i64 |

| 15 |

| 10 |

| 7 |

| 3 |

| 1 |

Tip

The return keyword causes a function to return a result immediately, without

running any subsequent code in its body. So before the end of the function, it

only makes sense to use return from inside of

Conditional Statements.

A function returns one object, but sometimes computations have multiple results. In that case, return the results in a container such as a tuple or list.

For example, let’s make a function that computes the mean and median for a vector. We’ll return the results in a tuple:

def compute_mean_med(x):

m1 = x.mean()

m2 = x.median()

return m1, m2

compute_mean_med(pl.Series([1, 2, 3, 1]))

(1.75, 1.5)

Tip

Before you write a function, it’s useful to go through several steps:

Write down what you want to do, in detail. It can also help to draw a picture of what needs to happen.

Check whether there’s already a built-in function. Search online and in the Python documentation.

Write the code to handle a simple case first. For data science problems, use a small dataset at this step.

Functions are the building blocks for solving larger problems. Take a divide-and-conquer approach, breaking large problems into smaller steps. Use a short function for each step. This approach makes it easier to:

Test that each step works correctly.

Modify, reuse, or repurpose a step.

4.2. Conditional Statements#

Sometimes you’ll need code to do different things depending on a condition. You can use an if-statement to write conditional code.

An if-statement begins with the if keyword, followed by a condition and a

colon :. The condition must be an expression that returns a Boolean value

(False or True). The body of the if-statement is the code that will run

when the condition is True. Code in the body must be indented by 4 spaces.

For example, suppose you want your code to generate a different greeting depending on an input name:

name = "Nick"

# Default greeting

greeting = "Nice to meet you!"

if name == "Nick":

greeting = "Hi Nick, nice to see you again!"

greeting

'Hi Nick, nice to see you again!'

Use the else keyword (and a colon :) if you want to add an alternative when

the condition is false. So the previous code can also be written as:

name = "Nick"

if name == "Nick":

greeting = "Hi Nick, nice to see you again!"

else:

# Default greeting

greeting = "Nice to meet you!"

greeting

'Hi Nick, nice to see you again!'

Use the elif keyword with a condition (and a colon :) if you want to add an

alternative to the first condition that also has its own condition. Only the

first case where a condition is True will run. You can use elif as many

times as you want, and can also use else. For example:

name = "Susan"

if name == "Nick":

greeting = "Hi Nick, nice to see you again!"

elif name == "Peter":

greeting = "Go away Peter, I'm busy!"

else:

greeting = "Nice to meet you!"

greeting

'Nice to meet you!'

You can create compound conditions with the keywords not, and and or. The

not keyword inverts a condition. The and keyword combines two conditions

and returns True only if both are True. The or keyword combines two

conditions and returns True if either or both are True.

For example:

name1 = "Arthur"

name2 = "Nick"

if name1 == "Arthur" and name2 == "Nick":

greeting = "These are the authors."

else:

greeting = "Who are these people?!"

greeting

'These are the authors.'

You can write an if-statement inside of another if-statement. This is called

nesting if-statements. Nesting is useful when you want to check a

condition, do some computations, and then check another condition under the

assumption that the first condition was True.

Tip

If-statements correspond to special cases in your code. Lots of special cases in code makes the code harder to understand and maintain. If you find yourself using lots of if-statements, especially nested if-statements, consider whether there is a more general strategy or way to write the code.

4.3. Iteration#

Python is powerful tool for automating tasks that have repetitive steps. For example, you can:

Apply a transformation to an entire column of data.

Compute distances between all pairs from a set of points.

Read a large collection of files from disk in order to combine and analyze the data they contain.

Simulate how a system evolves over time from a specific set of starting parameters.

Scrape data from the pages of a website.

You can implement concise, efficient solutions for these kinds of tasks in Python by using iteration, which means repeating a computation many times. Python provides four different strategies for writing iterative code:

Broadcasting, where a function is implicitly called on each element of a data structure. This was introduced in Broadcasting.

Comprehensions, where a function is explicitly called on each element of a vector or array. This was introduced in Comprehensions.

Loops, where an expression is evaluated repeatedly until some condition is met.

Recursion, where a function calls itself.

Broadcasting is the most efficient and most concise iteration strategy, but also the least flexible, because it only works with a few functions and data structures. Comprehensions are more flexible—they work with any function and any data structure with elements—but less efficient and less concise. Loops and recursion provide the most flexibility but are the least concise. In recent versions of Python, comprehensions are slightly more efficient than loops. Recursion tends to be the least efficient iteration strategy in Python.

The rest of this section explains how to write loops and how to choose which iteration strategy to use. We assume you’re already comfortable with broadcasting and have at least some familiarity with comprehensions.

4.3.1. For-Loops#

A for-loop evaluates the expressions in its body once for each element of a

data structure. A for-loop begins with the for keyword, followed by:

A placeholder variable, which will be automatically signed to an element at the beginning of each iteration

The

inkeywordAn object with elements

A colon

:

Code in the body of the loop must be indented by 4 spaces.

For example, to print out all the column names in terns.columns, you can

write:

for column in terns.columns:

print(column)

year

site_name

site_name_2013_2018

site_name_1988_2001

site_abbr

region_3

region_4

event

bp_min

bp_max

fl_min

fl_max

total_nests

nonpred_eggs

nonpred_chicks

nonpred_fl

nonpred_ad

pred_control

pred_eggs

pred_chicks

pred_fl

pred_ad

pred_pefa

pred_coy_fox

pred_meso

pred_owlspp

pred_corvid

pred_other_raptor

pred_other_avian

pred_misc

total_pefa

total_coy_fox

total_meso

total_owlspp

total_corvid

total_other_raptor

total_other_avian

total_misc

first_observed

last_observed

first_nest

first_chick

first_fledge

Within the indented part of a for-loop, you can compute values, check conditions, etc.

Oftentimes you want to save the result of the code you perform within a

for-loop. The easiest way to do this is by creating an empty list and using

append to add values to it.

diffs = []

values = [10, 12, 11, 2, 3]

for a, b in zip(values[:-1], values[1:]):

diffs.append(a - b)

diffs

[-2, 1, 9, -1]

4.3.2. Planning for Iteration#

At first it might seem difficult to decide if and what kind of iteration to use. Start by thinking about whether you need to do something over and over. If you don’t, then you probably don’t need to use iteration. If you do, then try iteration strategies in this order:

Broadcasting

Comprehensions

Try a comprehension if iterations are independent.

Loops

Try a for-loop if some iterations depend on others.

Recursion (which isn’t covered here)

Convenient for naturally recursive tasks (like Fibonacci), but often there are faster solutions.

Start by writing the code for just one iteration. Make sure that code works; it’s easy to test code for one iteration.

When you have one iteration working, then try using the code with an iteration

strategy (you will have to make some small changes). If it doesn’t work, try to

figure out which iteration is causing the problem. One way to do this is to use

print to print out information. Then try to write the code for the broken

iteration, get that iteration working, and repeat this whole process.

4.4. Case Study: CA Hospital Utilization#

The California Department of Health Care Access and Information (HCAI) requires hospitals in the state to submit detailed information each year about how many beds they have and the total number of days for which each bed was occupied. The HCAI publishes the data to the California Open Data Portal. Let’s use Python to read data from 2016 to 2023 and investigate whether hospital utilization is noticeably different in and after 2020.

The data set consists of a separate Microsoft Excel file for each year. Before 2018, HCAI used a data format (in Excel) called ALIRTS. In 2018, they started collecting more data and switched to a data format called SIERA. The 2018 data file contains a crosswalk that shows the correspondence between SIERA columns and ALIRTS columns.

Important

Click here to download the CA Hospital Utilization data set (8 Excel files).

If you haven’t already, we recommend you create a directory for this workshop.

In your workshop directory, create a data/ca_hospitals subdirectory. Download

and save the data set in the data/ca_hospitals subdirectory.

When you need to solve a programming problem, get started by writing some comments that describe the problem, the inputs, and the expected output. Try to be concrete. This will help you clarify what you’re trying to achieve and serve as a guiding light while you work.

As a programmer (or any kind of problem-solver), you should always be on the lookout for ways to break problems into smaller, simpler steps. Think about this when you frame a problem. Small steps are easier to reason about, implement, and test. When you complete one, you also get a nice sense of progress towards your goal.

For the CA Hospital Utilization data set, our goal is to investigate whether there was a change in hospital utilization in 2020. Before we can do any investigation, we need to read the files into Python. The files all contain tabular data and have similar formats, so let’s try to combine them into a single data frame. We’ll say this in the framing comments:

# Read the CA Hospital Utilization data set into Python. The inputs are

# yearly Excel files (2016-2023) that need to be combined. The pre-2018 files

# have a different format from the others. The result should be a single data

# frame with information about bed and patient counts.

#

# After reading the data set, we'll investigate utilization in 2020.

“Investigate utilization” is a little vague, but for an exploratory data analysis, it’s hard to say exactly what to do until you’ve started working with the data.

We need to read multiple files, but we can simplify the problem by starting

with just one. Let’s start with the 2023 data. It’s in an Excel file, which you

can read with Polars’ pl.read_excel function (note: you’ll first need to

install the fastexcel package). The function requires the path to the file; you

can also optionally provide the sheet name or number (starting from 1). Open up

the Excel file in your computer’s spreadsheet program and take a look. There

are multiple sheets, and the data about beds and patients are in the second

sheet. Back in Python, read just the second sheet:

path = "data/ca_hospitals/hosp23_util_data_final.xlsx"

sheet = pl.read_excel(path, sheet_id=2)

sheet.head()

| Description | FAC_NO | FAC_NAME | FAC_STR_ADDR | FAC_CITY | FAC_ZIP | FAC_PHONE | FAC_ADMIN_NAME | FAC_OPERATED_THIS_YR | FAC_OP_PER_BEGIN_DT | FAC_OP_PER_END_DT | FAC_PAR_CORP_NAME | FAC_PAR_CORP_BUS_ADDR | FAC_PAR_CORP_CITY | FAC_PAR_CORP_STATE | FAC_PAR_CORP_ZIP | REPT_PREP_NAME | SUBMITTED_DT | REV_REPT_PREP_NAME | REVISED_DT | CORRECTED_DT | LICENSE_NO | LICENSE_EFF_DATE | LICENSE_EXP_DATE | LICENSE_STATUS | FACILITY_LEVEL | TRAUMA_CTR | TEACH_HOSP | TEACH_RURAL | LONGITUDE | LATITUDE | ASSEMBLY_DIST | SENATE_DIST | CONGRESS_DIST | CENSUS_KEY | MED_SVC_STUDY_AREA | LA_COUNTY_SVC_PLAN_AREA | … | EQUIP_VAL_05 | EQUIP_VAL_06 | EQUIP_VAL_07 | EQUIP_VAL_08 | EQUIP_VAL_09 | EQUIP_VAL_10 | PROJ_EXPENDITURES_01 | PROJ_EXPENDITURES_02 | PROJ_EXPENDITURES_03 | PROJ_EXPENDITURES_04 | PROJ_EXPENDITURES_05 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_01 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_02 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_03 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_04 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_05 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_06 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_07 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_08 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_09 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_10 | HCAI_PROJ_NO_01 | HCAI_PROJ_NO_02 | HCAI_PROJ_NO_03 | HCAI_PROJ_NO_04 | HCAI_PROJ_NO_05 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_01 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_02 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_03 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_04 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_05 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_06 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_07 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_08 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_09 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_10 | __UNNAMED__354 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | … | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str |

| "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | … | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… | "FINAL 2023 UTILIZATION DATABAS… |

| "Page" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | … | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | "6.0" | null |

| "Column" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | … | "2.0" | "2.0" | "2.0" | "2.0" | "2.0" | "2.0" | "2.0" | "2.0" | "2.0" | "2.0" | "2.0" | "3.0" | "3.0" | "3.0" | "3.0" | "3.0" | "3.0" | "3.0" | "3.0" | "3.0" | "3.0" | "3.0" | "3.0" | "3.0" | "3.0" | "3.0" | "4.0" | "4.0" | "4.0" | "4.0" | "4.0" | "4.0" | "4.0" | "4.0" | "4.0" | "4.0" | null |

| "Line" | "2.0" | "1.0" | "3.0" | "4.0" | "5.0" | "6.0" | "7.0" | "9.0" | "10.0" | "11.0" | "12.0" | "13.0" | "14.0" | "15.0" | "16.0" | "20.0" | "24.0" | "25.0" | "29.0" | "30.0" | "100.0" | "101.0" | "102.0" | "103.0" | "104.0" | "105.0" | "106.0" | "107.0" | "108.0" | "109.0" | "110.0" | "111.0" | "112.0" | "113.0" | "114.0" | "115.0" | … | "6.0" | "7.0" | "8.0" | "9.0" | "10.0" | "11.0" | "26.0" | "27.0" | "28.0" | "29.0" | "30.0" | "2.0" | "3.0" | "4.0" | "5.0" | "6.0" | "7.0" | "8.0" | "9.0" | "10.0" | "11.0" | "26.0" | "27.0" | "28.0" | "29.0" | "30.0" | "2.0" | "3.0" | "4.0" | "5.0" | "6.0" | "7.0" | "8.0" | "9.0" | "10.0" | "11.0" | null |

| null | "106010735" | "ALAMEDA HOSPITAL" | "2070 CLINTON AVE" | "ALAMEDA" | "94501" | "5102333700" | "Mario Harding" | "Yes" | "2023-01-01 00:00:00" | "2023-12-31 00:00:00" | "Alameda Health System" | "1431 East 31st Street" | "Oakland" | "CA - California" | "94602" | "Ramneet Kaur" | "2024-02-14 16:11:00" | "Ramneet Kaur" | "02/15/2024 01:35 PM" | null | "140000002" | "2023-05-01 00:00:00" | "2024-04-30 00:00:00" | "Open" | "Parent Facility" | null | "No" | "No" | "-122.253491" | "37.762781" | "District 18" | "District 7" | "District 12" | "06001428500" | "2e" | null | … | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null |

The first four rows contain metadata about the columns; the first hospital, Alameda Hospital, is listed in the fifth row. So let’s remove the first four rows:

sheet = sheet[4:, :]

sheet.head()

| Description | FAC_NO | FAC_NAME | FAC_STR_ADDR | FAC_CITY | FAC_ZIP | FAC_PHONE | FAC_ADMIN_NAME | FAC_OPERATED_THIS_YR | FAC_OP_PER_BEGIN_DT | FAC_OP_PER_END_DT | FAC_PAR_CORP_NAME | FAC_PAR_CORP_BUS_ADDR | FAC_PAR_CORP_CITY | FAC_PAR_CORP_STATE | FAC_PAR_CORP_ZIP | REPT_PREP_NAME | SUBMITTED_DT | REV_REPT_PREP_NAME | REVISED_DT | CORRECTED_DT | LICENSE_NO | LICENSE_EFF_DATE | LICENSE_EXP_DATE | LICENSE_STATUS | FACILITY_LEVEL | TRAUMA_CTR | TEACH_HOSP | TEACH_RURAL | LONGITUDE | LATITUDE | ASSEMBLY_DIST | SENATE_DIST | CONGRESS_DIST | CENSUS_KEY | MED_SVC_STUDY_AREA | LA_COUNTY_SVC_PLAN_AREA | … | EQUIP_VAL_05 | EQUIP_VAL_06 | EQUIP_VAL_07 | EQUIP_VAL_08 | EQUIP_VAL_09 | EQUIP_VAL_10 | PROJ_EXPENDITURES_01 | PROJ_EXPENDITURES_02 | PROJ_EXPENDITURES_03 | PROJ_EXPENDITURES_04 | PROJ_EXPENDITURES_05 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_01 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_02 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_03 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_04 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_05 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_06 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_07 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_08 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_09 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_10 | HCAI_PROJ_NO_01 | HCAI_PROJ_NO_02 | HCAI_PROJ_NO_03 | HCAI_PROJ_NO_04 | HCAI_PROJ_NO_05 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_01 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_02 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_03 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_04 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_05 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_06 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_07 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_08 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_09 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_10 | __UNNAMED__354 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | … | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str |

| null | "106010735" | "ALAMEDA HOSPITAL" | "2070 CLINTON AVE" | "ALAMEDA" | "94501" | "5102333700" | "Mario Harding" | "Yes" | "2023-01-01 00:00:00" | "2023-12-31 00:00:00" | "Alameda Health System" | "1431 East 31st Street" | "Oakland" | "CA - California" | "94602" | "Ramneet Kaur" | "2024-02-14 16:11:00" | "Ramneet Kaur" | "02/15/2024 01:35 PM" | null | "140000002" | "2023-05-01 00:00:00" | "2024-04-30 00:00:00" | "Open" | "Parent Facility" | null | "No" | "No" | "-122.253491" | "37.762781" | "District 18" | "District 7" | "District 12" | "06001428500" | "2e" | null | … | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null |

| null | "106010739" | "ALTA BATES SUMMIT MEDICAL CENT… | "2450 ASHBY AVENUE" | "BERKELEY" | "94705" | "510-655-4000" | "David D. Clark, Chief Executiv… | "Yes" | "2023-01-01 00:00:00" | "2023-12-31 00:00:00" | "Sutter Health" | "2000 Powell Street, 10th Floo… | "Emeryville" | "CA - California" | "94608" | "Jeannie Cornelius" | "2024-02-15 18:55:00" | null | null | null | "140000004" | "2023-11-01 00:00:00" | "2024-10-31 00:00:00" | "Open" | "Parent Facility" | null | "No" | "No" | "-122.257501" | "37.855628" | "District 14" | "District 7" | "District 12" | "06001423902" | "2b" | null | … | null | null | null | null | null | null | "3451229" | null | null | null | null | "2023-03-23 00:00:00" | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | "Purchase" | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null |

| null | "106010776" | "UCSF BENIOFF CHILDREN'S HOSPIT… | "747 52ND STREET" | "OAKLAND" | "94609" | "510-428-3000" | "Joan Zoltanski" | "Yes" | "2023-01-01 00:00:00" | "2023-12-31 00:00:00" | null | null | null | null | null | "LAURA CHERRY" | "2024-02-15 14:02:00" | null | null | null | "140000015" | "2023-05-17 00:00:00" | "2023-12-31 00:00:00" | "Open" | "Parent Facility" | "Level I - Pediatric" | "No" | "No" | "-122.267028" | "37.83719" | "District 18" | "District 7" | "District 12" | "06001401000" | "2c" | null | … | null | null | null | null | null | null | "106700000" | "3500000" | "2935000" | "6388650" | null | "2023-09-30 00:00:00" | "2023-11-30 00:00:00" | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | "Purchase" | "Purchase" | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null |

| null | "106010811" | "FAIRMONT HOSPITAL" | "15400 FOOTHILL BOULEVARD" | "SAN LEANDRO" | "94578" | "5104374800" | "Richard Espinoza" | "Yes" | "2023-01-01 00:00:00" | "2023-12-31 00:00:00" | "Alameda Health System" | "1431 East 31st Street" | "Oakland" | "CA - California" | "94702" | "Ramneet Kaur" | "2024-02-12 11:58:00" | null | null | null | "140000046" | "2023-11-01 00:00:00" | "2024-10-31 00:00:00" | "Open" | "Consolidated Facility" | null | "No" | "No" | "-122.119823" | "37.708168" | "District 20" | "District 9" | "District 14" | "06001430500" | "2f" | null | … | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null |

| null | "106010844" | "ALTA BATES SUMMIT MEDICAL CENT… | "2001 DWIGHT WAY" | "BERKELEY" | "94704" | "510-655-4000" | "David D. Clark, Chief Executiv… | "Yes" | "2023-01-01 00:00:00" | "2023-12-31 00:00:00" | "Sutter Health" | "2000 Powell Street, 10th Floo… | "Emeryville" | "CA - California" | "94608" | "Jeannie Cornelius" | "2024-02-15 18:55:00" | null | null | null | "140000004" | "2023-11-01 00:00:00" | "2024-10-31 00:00:00" | "Open" | "Consolidated Facility" | null | "No" | "No" | "-122.268712" | "37.864072" | "District 14" | "District 7" | "District 12" | "06001422900" | "2a" | null | … | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null |

Some data sets also have metadata in the last rows, so let’s check for that here:

sheet.tail()

| Description | FAC_NO | FAC_NAME | FAC_STR_ADDR | FAC_CITY | FAC_ZIP | FAC_PHONE | FAC_ADMIN_NAME | FAC_OPERATED_THIS_YR | FAC_OP_PER_BEGIN_DT | FAC_OP_PER_END_DT | FAC_PAR_CORP_NAME | FAC_PAR_CORP_BUS_ADDR | FAC_PAR_CORP_CITY | FAC_PAR_CORP_STATE | FAC_PAR_CORP_ZIP | REPT_PREP_NAME | SUBMITTED_DT | REV_REPT_PREP_NAME | REVISED_DT | CORRECTED_DT | LICENSE_NO | LICENSE_EFF_DATE | LICENSE_EXP_DATE | LICENSE_STATUS | FACILITY_LEVEL | TRAUMA_CTR | TEACH_HOSP | TEACH_RURAL | LONGITUDE | LATITUDE | ASSEMBLY_DIST | SENATE_DIST | CONGRESS_DIST | CENSUS_KEY | MED_SVC_STUDY_AREA | LA_COUNTY_SVC_PLAN_AREA | … | EQUIP_VAL_05 | EQUIP_VAL_06 | EQUIP_VAL_07 | EQUIP_VAL_08 | EQUIP_VAL_09 | EQUIP_VAL_10 | PROJ_EXPENDITURES_01 | PROJ_EXPENDITURES_02 | PROJ_EXPENDITURES_03 | PROJ_EXPENDITURES_04 | PROJ_EXPENDITURES_05 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_01 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_02 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_03 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_04 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_05 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_06 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_07 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_08 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_09 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_10 | HCAI_PROJ_NO_01 | HCAI_PROJ_NO_02 | HCAI_PROJ_NO_03 | HCAI_PROJ_NO_04 | HCAI_PROJ_NO_05 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_01 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_02 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_03 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_04 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_05 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_06 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_07 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_08 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_09 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_10 | __UNNAMED__354 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | … | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str |

| null | "106580996" | "ADVENTIST HEALTH AND RIDEOUT" | "726 FOURTH ST" | "MARYSVILLE" | "95901" | "530-751-4300" | "Chris Champlin" | "Yes" | "2023-01-01 00:00:00" | "2023-12-31 00:00:00" | null | null | null | null | null | "Erika Collazo" | "2024-02-15 17:09:00" | null | null | null | "230000126" | "2023-11-01 00:00:00" | "2024-10-31 00:00:00" | "Open" | "Parent Facility" | "Level III" | "No" | "No" | "-121.594228" | "39.138174" | "District 3" | "District 1" | "District 1" | "06115040100" | "249" | null | … | null | null | null | null | null | null | "2000000" | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null |

| null | "206100718" | "COMMUNITY SUBACUTE AND TRANSIT… | "3003 NORTH MARIPOSA STREET" | "FRESNO" | "93703" | "559-459-1844" | "Leslie Cotham" | "No" | "2023-01-01 00:00:00" | "2023-12-31 00:00:00" | "Fresno Community Hospital and … | "789 N Medical Center Drive Eas… | "Clovis" | "CA - California" | "93611" | "Irma Lorenzo" | "2024-02-15 16:08:00" | null | null | null | "040000096" | "2023-11-07 00:00:00" | "2024-11-06 00:00:00" | "Open" | "Distinct Part Facility" | null | "No" | "No" | "-119.779788" | "36.777715" | "District 31" | "District 14" | "District 21" | "06019003400" | "35c" | null | … | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null |

| null | "206274027" | "WESTLAND HOUSE" | "100 BARNET SEGAL LANE" | "MONTEREY" | "93940" | "8316245311" | "Dr. Steven Packer" | "No" | "2023-01-01 00:00:00" | "2023-12-31 00:00:00" | "Montage Health" | "PO Box HH" | "Monterey" | "CA - California" | "93940" | "John W. Thibeau" | "2024-02-19 15:45:00" | null | null | null | "070000026" | "2023-12-01 00:00:00" | "2024-11-30 00:00:00" | "Open" | "Distinct Part Facility" | null | "No" | "No" | "-121.885834" | "36.5812" | "District 30" | "District 17" | "District 19" | "06053013200" | "110" | null | … | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null |

| null | "206351814" | "HAZEL HAWKINS MEMORIAL HOSPITA… | "900 SUNSET DRIVE" | "HOLLISTER" | "95023" | "831-635-1106" | "Mary Casillas" | "Yes" | "2023-01-01 00:00:00" | "2023-12-31 00:00:00" | "San Benito Health Care Distric… | "911 Sunset Drive" | "Hollister" | "CA - California" | "95023" | "SANDRA DILAURA" | "2024-02-21 15:35:00" | null | null | null | "070000004" | "2023-01-01 00:00:00" | "2023-12-31 00:00:00" | "Open" | "Distinct Part Facility" | null | "No" | "No" | "-121.386815" | "36.83558" | "District 29" | "District 17" | "District 18" | "06069000600" | "140" | null | … | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null |

| null | null | "n = 506" | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | … | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null |

Sure enough, the last row contains what appears to be a count of the hospitals rather than a hospital. Let’s remove it by indexing with a negative value, which counts backward from the end:

sheet = sheet[:-1, :]

sheet.tail()

| Description | FAC_NO | FAC_NAME | FAC_STR_ADDR | FAC_CITY | FAC_ZIP | FAC_PHONE | FAC_ADMIN_NAME | FAC_OPERATED_THIS_YR | FAC_OP_PER_BEGIN_DT | FAC_OP_PER_END_DT | FAC_PAR_CORP_NAME | FAC_PAR_CORP_BUS_ADDR | FAC_PAR_CORP_CITY | FAC_PAR_CORP_STATE | FAC_PAR_CORP_ZIP | REPT_PREP_NAME | SUBMITTED_DT | REV_REPT_PREP_NAME | REVISED_DT | CORRECTED_DT | LICENSE_NO | LICENSE_EFF_DATE | LICENSE_EXP_DATE | LICENSE_STATUS | FACILITY_LEVEL | TRAUMA_CTR | TEACH_HOSP | TEACH_RURAL | LONGITUDE | LATITUDE | ASSEMBLY_DIST | SENATE_DIST | CONGRESS_DIST | CENSUS_KEY | MED_SVC_STUDY_AREA | LA_COUNTY_SVC_PLAN_AREA | … | EQUIP_VAL_05 | EQUIP_VAL_06 | EQUIP_VAL_07 | EQUIP_VAL_08 | EQUIP_VAL_09 | EQUIP_VAL_10 | PROJ_EXPENDITURES_01 | PROJ_EXPENDITURES_02 | PROJ_EXPENDITURES_03 | PROJ_EXPENDITURES_04 | PROJ_EXPENDITURES_05 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_01 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_02 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_03 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_04 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_05 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_06 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_07 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_08 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_09 | DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_10 | HCAI_PROJ_NO_01 | HCAI_PROJ_NO_02 | HCAI_PROJ_NO_03 | HCAI_PROJ_NO_04 | HCAI_PROJ_NO_05 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_01 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_02 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_03 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_04 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_05 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_06 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_07 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_08 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_09 | MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_10 | __UNNAMED__354 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | … | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str |

| null | "106574010" | "SUTTER DAVIS HOSPITAL" | "2000 SUTTER PLACE" | "DAVIS" | "95616" | "(530) 756-6440" | "Michael Cureton" | "Yes" | "2023-01-01 00:00:00" | "2023-12-31 00:00:00" | "Sutter Health" | "2300 River Plaza Dr" | "Sacramento" | "CA - California" | "95833" | "Luke D. Peterson" | "2024-01-25 11:04:00" | null | null | null | "030000124" | "2023-06-05 00:00:00" | "2024-05-30 00:00:00" | "Open" | "Parent Facility" | null | "No" | "No" | "-121.770684" | "38.562688" | "District 4" | "District 3" | "District 4" | "06113010505" | "244" | null | … | null | null | null | null | null | null | "4847000" | "1999354" | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null |

| null | "106580996" | "ADVENTIST HEALTH AND RIDEOUT" | "726 FOURTH ST" | "MARYSVILLE" | "95901" | "530-751-4300" | "Chris Champlin" | "Yes" | "2023-01-01 00:00:00" | "2023-12-31 00:00:00" | null | null | null | null | null | "Erika Collazo" | "2024-02-15 17:09:00" | null | null | null | "230000126" | "2023-11-01 00:00:00" | "2024-10-31 00:00:00" | "Open" | "Parent Facility" | "Level III" | "No" | "No" | "-121.594228" | "39.138174" | "District 3" | "District 1" | "District 1" | "06115040100" | "249" | null | … | null | null | null | null | null | null | "2000000" | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null |

| null | "206100718" | "COMMUNITY SUBACUTE AND TRANSIT… | "3003 NORTH MARIPOSA STREET" | "FRESNO" | "93703" | "559-459-1844" | "Leslie Cotham" | "No" | "2023-01-01 00:00:00" | "2023-12-31 00:00:00" | "Fresno Community Hospital and … | "789 N Medical Center Drive Eas… | "Clovis" | "CA - California" | "93611" | "Irma Lorenzo" | "2024-02-15 16:08:00" | null | null | null | "040000096" | "2023-11-07 00:00:00" | "2024-11-06 00:00:00" | "Open" | "Distinct Part Facility" | null | "No" | "No" | "-119.779788" | "36.777715" | "District 31" | "District 14" | "District 21" | "06019003400" | "35c" | null | … | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null |

| null | "206274027" | "WESTLAND HOUSE" | "100 BARNET SEGAL LANE" | "MONTEREY" | "93940" | "8316245311" | "Dr. Steven Packer" | "No" | "2023-01-01 00:00:00" | "2023-12-31 00:00:00" | "Montage Health" | "PO Box HH" | "Monterey" | "CA - California" | "93940" | "John W. Thibeau" | "2024-02-19 15:45:00" | null | null | null | "070000026" | "2023-12-01 00:00:00" | "2024-11-30 00:00:00" | "Open" | "Distinct Part Facility" | null | "No" | "No" | "-121.885834" | "36.5812" | "District 30" | "District 17" | "District 19" | "06053013200" | "110" | null | … | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null |

| null | "206351814" | "HAZEL HAWKINS MEMORIAL HOSPITA… | "900 SUNSET DRIVE" | "HOLLISTER" | "95023" | "831-635-1106" | "Mary Casillas" | "Yes" | "2023-01-01 00:00:00" | "2023-12-31 00:00:00" | "San Benito Health Care Distric… | "911 Sunset Drive" | "Hollister" | "CA - California" | "95023" | "SANDRA DILAURA" | "2024-02-21 15:35:00" | null | null | null | "070000004" | "2023-01-01 00:00:00" | "2023-12-31 00:00:00" | "Open" | "Distinct Part Facility" | null | "No" | "No" | "-121.386815" | "36.83558" | "District 29" | "District 17" | "District 18" | "06069000600" | "140" | null | … | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | null |

There are a lot of columns in sheet, so let’s make a list of just a few that we’ll use for analysis. We’ll keep:

Columns with facility name, location, and operating status

All of the columns whose names start with

TOT, because these are totals for number of beds, number of census-days, and so on.Columns about acute respiratory beds, with names that contain

RESPIRATORY, because they might also be relevant.

We can get all of these columns with the .select method. The TOT and

RESPIRATORY columns all contain numbers, but the element type is str, so

we’ll cast them to floats. We’ll also add a column with the year:

facility_cols = pl.col(

"FAC_NAME", "FAC_CITY", "FAC_ZIP", "FAC_OPERATED_THIS_YR", "FACILITY_LEVEL",

"TEACH_HOSP", "COUNTY", "PRIN_SERVICE_TYPE",

)

sheet = sheet.select(

pl.lit(2023).alias("year"),

facility_cols,

pl.col("^TOT.*$", "^.*RESPIRATORY.*$").cast(pl.Float64),

)

sheet.head()

| year | FAC_NAME | FAC_CITY | FAC_ZIP | FAC_OPERATED_THIS_YR | FACILITY_LEVEL | TEACH_HOSP | COUNTY | PRIN_SERVICE_TYPE | TOT_LIC_BEDS | TOT_LIC_BED_DAYS | TOT_DISCHARGES | TOT_CEN_DAYS | TOT_ALOS_CY | TOT_ALOS_PY | ACUTE_RESPIRATORY_CARE_LIC_BEDS | ACUTE_RESPIRATORY_CARE_LIC_BED_DAYS | ACUTE_RESPIRATORY_CARE_DISCHARGES | ACUTE_RESPIRATORY_CARE_INTRA_TRANSFERS | ACUTE_RESPIRATORY_CARE_CEN_DAYS | ACUTE_RESPIRATORY_CARE_ALOS_CY | ACUTE_RESPIRATORY_CARE_ALOS_PY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i32 | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 |

| 2023 | "ALAMEDA HOSPITAL" | "ALAMEDA" | "94501" | "Yes" | "Parent Facility" | "No" | "Alameda" | "General Medical / Surgical" | 247.0 | 90155.0 | 2974.0 | 66163.0 | 22.2 | 24.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | null | null | null | null | 0.0 |

| 2023 | "ALTA BATES SUMMIT MEDICAL CENT… | "BERKELEY" | "94705" | "Yes" | "Parent Facility" | "No" | "Alameda" | "General Medical / Surgical" | 339.0 | 123735.0 | 11295.0 | 56442.0 | 5.0 | 4.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | null | null | null | null | 0.0 |

| 2023 | "UCSF BENIOFF CHILDREN'S HOSPIT… | "OAKLAND" | "94609" | "Yes" | "Parent Facility" | "No" | "Alameda" | "Pediatric" | 155.0 | 59465.0 | 7537.0 | 40891.0 | 5.4 | 5.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | null | null | null | null | 0.0 |

| 2023 | "FAIRMONT HOSPITAL" | "SAN LEANDRO" | "94578" | "Yes" | "Consolidated Facility" | "No" | "Alameda" | "Long-Term Care (SN / IC)" | 109.0 | 39785.0 | 176.0 | 45336.0 | 257.6 | 371.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | null | null | null | null | 0.0 |

| 2023 | "ALTA BATES SUMMIT MEDICAL CENT… | "BERKELEY" | "94704" | "Yes" | "Consolidated Facility" | "No" | "Alameda" | "Psychiatric" | 64.0 | 24576.0 | 1853.0 | 17413.0 | 9.4 | 10.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | null | null | null | null | 0.0 |

Lowercase names are easier to type, so let’s also make all of the names

lowercase with the .rename and str.lower methods:

sheet = sheet.rename(str.lower)

sheet.head()

| year | fac_name | fac_city | fac_zip | fac_operated_this_yr | facility_level | teach_hosp | county | prin_service_type | tot_lic_beds | tot_lic_bed_days | tot_discharges | tot_cen_days | tot_alos_cy | tot_alos_py | acute_respiratory_care_lic_beds | acute_respiratory_care_lic_bed_days | acute_respiratory_care_discharges | acute_respiratory_care_intra_transfers | acute_respiratory_care_cen_days | acute_respiratory_care_alos_cy | acute_respiratory_care_alos_py |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i32 | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 |

| 2023 | "ALAMEDA HOSPITAL" | "ALAMEDA" | "94501" | "Yes" | "Parent Facility" | "No" | "Alameda" | "General Medical / Surgical" | 247.0 | 90155.0 | 2974.0 | 66163.0 | 22.2 | 24.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | null | null | null | null | 0.0 |

| 2023 | "ALTA BATES SUMMIT MEDICAL CENT… | "BERKELEY" | "94705" | "Yes" | "Parent Facility" | "No" | "Alameda" | "General Medical / Surgical" | 339.0 | 123735.0 | 11295.0 | 56442.0 | 5.0 | 4.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | null | null | null | null | 0.0 |

| 2023 | "UCSF BENIOFF CHILDREN'S HOSPIT… | "OAKLAND" | "94609" | "Yes" | "Parent Facility" | "No" | "Alameda" | "Pediatric" | 155.0 | 59465.0 | 7537.0 | 40891.0 | 5.4 | 5.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | null | null | null | null | 0.0 |

| 2023 | "FAIRMONT HOSPITAL" | "SAN LEANDRO" | "94578" | "Yes" | "Consolidated Facility" | "No" | "Alameda" | "Long-Term Care (SN / IC)" | 109.0 | 39785.0 | 176.0 | 45336.0 | 257.6 | 371.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | null | null | null | null | 0.0 |

| 2023 | "ALTA BATES SUMMIT MEDICAL CENT… | "BERKELEY" | "94704" | "Yes" | "Consolidated Facility" | "No" | "Alameda" | "Psychiatric" | 64.0 | 24576.0 | 1853.0 | 17413.0 | 9.4 | 10.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | null | null | null | null | 0.0 |

We’ve successfully read one of the files! Since the 2018-2023 files all have

the same format, it’s likely that we can use almost the same code for all of

them. Any time you want to reuse code, it’s a sign that you should write a

function, so that’s what we’ll do. We’ll take all of the code we have so far

and put it in the body of a function called read_hospital_data, adding some

comments to indicate the steps and a return statement at the end:

def read_hospital_data():

# Read the 2nd sheet of the file.

path = "data/ca_hospitals/hosp23_util_data_final.xlsx"

sheet = pl.read_excel(path, sheet_id=2)

# Remove the first 4 and last row.

sheet = sheet[4:, :]

sheet = sheet[:-1, :]

# Select only a few columns of interest.

facility_cols = pl.col(

"FAC_NAME", "FAC_CITY", "FAC_ZIP", "FAC_OPERATED_THIS_YR",

"FACILITY_LEVEL", "TEACH_HOSP", "COUNTY", "PRIN_SERVICE_TYPE",

)

sheet = sheet.select(

pl.lit(2023).alias("year"),

facility_cols,

pl.col("^TOT.*$", "^.*RESPIRATORY.*$").cast(pl.Float64),

)

# Rename the columns to lowercase.

sheet = sheet.rename(str.lower)

return sheet

As it is, the function still only reads the 2023 file. The other files have

different paths, so the first thing we need to do is make the path variable a

parameter. We’ll also make a year parameter, for the year value inserted as a

column:

def read_hospital_data(path, year):

# Read the 2nd sheet of the file.

sheet = pl.read_excel(path, sheet_id=2)

# Remove the first 4 and last row.

sheet = sheet[4:-1, :]

# Select only a few columns of interest.

facility_cols = pl.col(

"FAC_NAME", "FAC_CITY", "FAC_ZIP", "FAC_OPERATED_THIS_YR",

"FACILITY_LEVEL", "TEACH_HOSP", "COUNTY", "PRIN_SERVICE_TYPE",

)

sheet = sheet.select(

pl.lit(year).alias("year"),

facility_cols,

pl.col("^TOT.*$", "^.*RESPIRATORY.*$").cast(pl.Float64),

)

# Rename the columns to lowercase.

sheet = sheet.rename(str.lower)

return sheet

Test the function out on a few of the files to make sure it works correctly:

read_hospital_data(

"data/ca_hospitals/hosp23_util_data_final.xlsx", 2023

).head()

| year | fac_name | fac_city | fac_zip | fac_operated_this_yr | facility_level | teach_hosp | county | prin_service_type | tot_lic_beds | tot_lic_bed_days | tot_discharges | tot_cen_days | tot_alos_cy | tot_alos_py | acute_respiratory_care_lic_beds | acute_respiratory_care_lic_bed_days | acute_respiratory_care_discharges | acute_respiratory_care_intra_transfers | acute_respiratory_care_cen_days | acute_respiratory_care_alos_cy | acute_respiratory_care_alos_py |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i32 | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 |

| 2023 | "ALAMEDA HOSPITAL" | "ALAMEDA" | "94501" | "Yes" | "Parent Facility" | "No" | "Alameda" | "General Medical / Surgical" | 247.0 | 90155.0 | 2974.0 | 66163.0 | 22.2 | 24.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | null | null | null | null | 0.0 |

| 2023 | "ALTA BATES SUMMIT MEDICAL CENT… | "BERKELEY" | "94705" | "Yes" | "Parent Facility" | "No" | "Alameda" | "General Medical / Surgical" | 339.0 | 123735.0 | 11295.0 | 56442.0 | 5.0 | 4.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | null | null | null | null | 0.0 |

| 2023 | "UCSF BENIOFF CHILDREN'S HOSPIT… | "OAKLAND" | "94609" | "Yes" | "Parent Facility" | "No" | "Alameda" | "Pediatric" | 155.0 | 59465.0 | 7537.0 | 40891.0 | 5.4 | 5.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | null | null | null | null | 0.0 |

| 2023 | "FAIRMONT HOSPITAL" | "SAN LEANDRO" | "94578" | "Yes" | "Consolidated Facility" | "No" | "Alameda" | "Long-Term Care (SN / IC)" | 109.0 | 39785.0 | 176.0 | 45336.0 | 257.6 | 371.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | null | null | null | null | 0.0 |

| 2023 | "ALTA BATES SUMMIT MEDICAL CENT… | "BERKELEY" | "94704" | "Yes" | "Consolidated Facility" | "No" | "Alameda" | "Psychiatric" | 64.0 | 24576.0 | 1853.0 | 17413.0 | 9.4 | 10.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | null | null | null | null | 0.0 |

read_hospital_data(

"data/ca_hospitals/hosp21_util_data_final-revised-06.15.2023.xlsx", 2021

).head()

| year | fac_name | fac_city | fac_zip | fac_operated_this_yr | facility_level | teach_hosp | county | prin_service_type | tot_lic_beds | tot_lic_bed_days | tot_discharges | tot_cen_days | tot_alos_cy | tot_alos_py | acute_respiratory_care_lic_beds | acute_respiratory_care_lic_bed_days | acute_respiratory_care_discharges | acute_respiratory_care_intra_transfers | acute_respiratory_care_cen_days | acute_respiratory_care_alos_cy | acute_respiratory_care_alos_py |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i32 | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 |

| 2021 | "ALAMEDA HOSPITAL" | "ALAMEDA" | "94501" | "Yes" | "Parent Facility" | "No" | "Alameda" | "General Medical / Surgical" | 247.0 | 90155.0 | 2431.0 | 66473.0 | 27.3 | 26.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | null | null | null | null | 0.0 |

| 2021 | "ALTA BATES SUMMIT MEDICAL CENT… | "BERKELEY" | "94705" | "Yes" | "Parent Facility" | "No" | "Alameda" | "General Medical / Surgical" | 339.0 | 123735.0 | 11344.0 | 53710.0 | 4.7 | 4.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | null | null | null | null | 0.0 |

| 2021 | "UCSF BENIOFF CHILDREN'S HOSPIT… | "OAKLAND" | "94609" | "Yes" | "Parent Facility" | "No" | "Alameda" | "Pediatric" | 215.0 | 78475.0 | 7256.0 | 38381.0 | 5.3 | 5.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | null | null | null | null | 0.0 |

| 2021 | "FAIRMONT HOSPITAL" | "SAN LEANDRO" | "94578" | "Yes" | "Consolidated Facility" | "No" | "Alameda" | "Long-Term Care (SN / IC)" | 109.0 | 39785.0 | 179.0 | 38652.0 | 215.9 | 542.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | null | null | null | null | 0.0 |

| 2021 | "ALTA BATES SUMMIT MEDICAL CENT… | "BERKELEY" | "94704" | "Yes" | "Consolidated Facility" | "No" | "Alameda" | "Psychiatric" | 68.0 | 24820.0 | 2236.0 | 19950.0 | 8.9 | 8.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | null | null | null | null | 0.0 |

The function appears to work correctly for two of the files, so let’s try it on

all of the 2018-2023 files. We can use the built-in pathlib module’s Path

class to help get a list of the files. The class’ .glob method does a

wildcard search for files:

from pathlib import Path

paths = Path("data/ca_hospitals/").glob("*.xlsx")

paths = list(paths)

paths

[PosixPath('data/ca_hospitals/hosp21_util_data_final-revised-06.15.2023.xlsx'),

PosixPath('data/ca_hospitals/hosp18_util_data_final.xlsx'),

PosixPath('data/ca_hospitals/hosp20_util_data_final-revised-06.15.2023.xlsx'),

PosixPath('data/ca_hospitals/hosp17_util_data_final.xlsx'),

PosixPath('data/ca_hospitals/hosp22_util_data_final_revised_11.28.2023.xlsx'),

PosixPath('data/ca_hospitals/hosp16_util_data_final.xlsx'),

PosixPath('data/ca_hospitals/hosp23_util_data_final.xlsx'),

PosixPath('data/ca_hospitals/hosp19_util_data_final.xlsx')]

In addition to the file paths, we also need the year for each file. Fortunately, the last two digits of the year are included in each file’s name. We can write a function to get these:

def get_hospital_year(path):

year = Path(path).name[4:6]

return int(year) + 2000

get_hospital_year(paths[0])

2021

Now we can use a for-loop to iterate over all of the files. We’ll skip the pre-2018 files for now:

hosps = []

for path in paths:

year = get_hospital_year(path)

# Only years 2018-2023.

if year >= 2018:

hosp = read_hospital_data(path, year)

hosps.append(hosp)

len(hosps)

6

With that working, we need to read the pre-2018 files. In the 2018 file, the fourth sheet is a crosswalk that shows which columns in the pre-2018 files correspond to columns in the later files. Let’s write some code to read the crosswalk. First, read the sheet:

cwalk = pl.read_excel(path, sheet_id=4)

cwalk.head()

| Page | Line | Column | SIERA Dataset Header (2019) | ALIRTS Dataset Header (2017) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i64 | i64 | i64 | str | str | str |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | "FAC_NAME" | "FAC_NAME" | null |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | "FAC_NO" | "OSHPD_ID" | null |

| 1 | 3 | 1 | "FAC_STR_ADDR" | null | "Address 1 and Address 2 combin… |

| 1 | 4 | 1 | "FAC_CITY" | "FAC_CITY" | null |

| 1 | 5 | 1 | "FAC_ZIP" | "FAC_ZIPCODE" | null |

The new and old column names are in the fourth and fifth columns, respectively, so we’ll get just those:

cwalk = cwalk[:, 3:5]

cwalk.head()

| SIERA Dataset Header (2019) | ALIRTS Dataset Header (2017) |

|---|---|

| str | str |

| "FAC_NAME" | "FAC_NAME" |

| "FAC_NO" | "OSHPD_ID" |

| "FAC_STR_ADDR" | null |

| "FAC_CITY" | "FAC_CITY" |

| "FAC_ZIP" | "FAC_ZIPCODE" |

Finally, use a comprehension to turn the cwalk data frame into a dictionary

with the old column names as the keys and the new column names as the values.

This way we can easily look up the new name for any of the old columns. Some of

the column names in cwalk have extra spaces at the end, so we’ll use .strip

method to remove them. We’ll also skip any rows where there’s no old column

name (because the column is only in the new data):

cwalk = {

old.strip(): new.strip()

for new, old in cwalk.iter_rows()

if old is not None

}

cwalk

{'FAC_NAME': 'FAC_NAME',

'OSHPD_ID': 'FAC_NO',

'FAC_CITY': 'FAC_CITY',

'FAC_ZIPCODE': 'FAC_ZIP',

'FAC_PHONE': 'FAC_PHONE',

'FAC_ADMIN_NAME': 'FAC_ADMIN_NAME',

'FAC_OPER_CURRYR': 'FAC_OPERATED_THIS_YR',

'BEG_DATE': 'FAC_OP_PER_BEGIN_DT',

'END_DATE': 'FAC_OP_PER_END_DT',

'PARENT_NAME': 'FAC_PAR_CORP_NAME',

'PARENT_CITY': 'FAC_PAR_CORP_CITY',

'PARENT_STATE': 'FAC_PAR_CORP_STATE',

'PARENT_ZIP_9': 'FAC_PAR_CORP_ZIP',

'REPORT_PREP_NAME': 'REPT_PREP_NAME',

'SUBMITTED_DT_TIME': 'SUBMITTED_DT',

'LICENSE_NO': 'LICENSE_NO',

'LIC_STATUS': 'LICENSE_STATUS',

'FACILITY_LEVEL': 'FACILITY_LEVEL',

'TRAUMA_CTR': 'TRAUMA_CTR',

'TEACH_HOSP': 'TEACH_HOSP',

'LONGITUDE': 'LONGITUDE',

'LATITUDE': 'LATITUDE',

'ASSEMBLY_DIST': 'ASSEMBLY_DIST',

'SENATE_DIST': 'SENATE_DIST',

'CONGRESS_DIST': 'CONGRESS_DIST',

'CENS_TRACT': 'CENS_TRACT',

'MED_SVC_STUDY_AREA': 'MED_SVC_STUDY_AREA',

'LACO_SVC_PLAN_AREA': 'LA_COUNTY_SVC_PLAN_AREA',

'HEALTH_SVC_AREA': 'HEALTH_SVC_AREA',

'COUNTY': 'COUNTY',

'TYPE_LIC': 'LIC_CAT',

'TYPE_CNTRL': 'LICEE_TOC',

'TYPE_SVC_PRINCIPAL': 'PRIN_SERVICE_TYPE',

'MED_SURG_LICBED_DAY': 'MED_SURG_LIC_BED_DAYS',

'MED_SURG_CENS_DAY': 'MED_SURG_CEN_DAYS',

'MED_SURG_DIS': 'MED_SURG_DISCHARGES',

'MED_SURG_BED_LIC': 'MED_SURG_LIC_BEDS',

'PERINATL_CENS_DAY': 'PERINATAL_CEN_DAYS',

'PERINATL_LICBED_DAY': 'PERINATAL_LIC_BED_DAYS',

'PERINATL_BED_LIC': 'PERINATAL_LIC_BEDS',

'PERINATL_DIS': 'PERINATAL_DISCHARGES',

'PED_CENS_DAY': 'PEDIATRIC_CEN_DAYS',

'PED_DIS': 'PEDIATRIC_DISCHARGES',

'PED_BED_LIC': 'PEDIATRIC_LIC_BEDS',

'PED_LICBED_DAY': 'PEDIATRIC_LIC_BED_DAYS',

'ICU_TFR_INHOSP': 'IC_INTRA_TRANSFERS',

'ICU_LICBED_DAY': 'IC_LIC_BED_DAYS',

'ICU_BED_LIC': 'IC_LIC_BEDS',

'ICU_CENS_DAY': 'IC_CEN_DAYS',

'ICU_DIS': 'IC_DISCHARGES',

'CCU_CENS_DAY': 'CORONARY_CARE_CEN_DAYS',

'CCU_BED_LIC': 'CORONARY_CARE_LIC_BEDS',

'CCU_LICBED_DAY': 'CORONARY_CARE_LIC_BED_DAYS',

'CCU_DIS': 'CORONARY_CARE_DISCHARGES',

'CCU_TFR_INHOSP': 'CORONARY_CARE_INTRA_TRANSFERS',

'RESP_DIS': 'ACUTE_RESPIRATORY_CARE_DISCHARGES',

'RESP_LICBED_DAY': 'ACUTE_RESPIRATORY_CARE_LIC_BED_DAYS',

'RESP_BED_LIC': 'ACUTE_RESPIRATORY_CARE_LIC_BEDS',

'RESP_CENS_DAY': 'ACUTE_RESPIRATORY_CARE_CEN_DAYS',

'RESP_TFR_INHOSP': 'ACUTE_RESPIRATORY_CARE_INTRA_TRANSFERS',

'BURN_LICBED_DAY': 'BURN_LIC_BED_DAYS',

'BURN_CENS_DAY': 'BURN_CEN_DAYS',

'BURN_DIS': 'BURN_DISCHARGES',

'BURN_TFR_INHOSP': 'BURN_INTRA_TRANSFERS',

'BURN_BED_LIC': 'BURN_LIC_BEDS',

'NICU_DIS': 'IC_NEWBORN_DISCHARGES',

'NICU_LICBED_DAY': 'IC_NEWBORN_LIC_BED_DAYS',

'NICU_BED_LIC': 'IC_NEWBORN_LIC_BEDS',

'NICU_CENS_DAY': 'IC_NEWBORN_CEN_DAYS',

'NICU_TFR_INHOSP': 'IC_NEWBORN_INTRA_TRANSFERS',

'REHAB_LICBED_DAY': 'REHAB_CTR_LIC_BED_DAYS',

'REHAB_CENS_DAY': 'REHAB_CTR_CEN_DAYS',

'REHAB_DIS': 'REHAB_CTR_DISCHARGES',

'REHAB_BED_LIC': 'REHAB_CTR_LIC_BEDS',

'GAC_DIS_SUBTOTL': 'GAC_SUBTOT_DISCHARGES',

'GAC_LICBED_DAY_SUBTOTL': 'GAC_SUBTOT_LIC_BED_DAYS',

'GAC_BED_LIC_SUBTOTL': 'GAC_SUBTOT_LIC_BEDS',

'GAC_CENS_DAY_SUBTOTL': 'GAC_SUBTOT_CEN_DAYS',

'CHEM_LICBED_DAY': 'CHEM_DEPEND_RECOVERY_LIC_BED_DAYS',

'CHEM_DIS': 'CHEM_DEPEND_RECOVERY_DISCHARGES',

'CHEM_CENS_DAY': 'CHEM_DEPEND_RECOV_CEN_DAYS',

'CHEM_BED_LIC': 'CHEM_DEPEND_RECOVERY_LIC_BEDS',

'PSY_BED_LIC': 'ACUTE_PSYCHIATRIC_LIC_BEDS',

'PSY_DIS': 'ACUTE_PSYCHIATRIC_DISCHARGES',

'PSY_CENS_DAY': 'ACUTE_PSYCHIATRIC_CEN_DAYS',

'PSY_LICBED_DAY': 'ACUTE_PSYCHIATRIC_LIC_BED_DAYS',

'SN_DIS': 'SN_DISCHARGES',

'SN_TFR_INHOSP': 'SN_INTRA_TRANSFERS',

'SN_LICBED_DAY': 'SN_LIC_BED_DAYS',

'SN_CENS_DAY': 'SN_CEN_DAYS',

'SN_BED_LIC': 'SN_LIC_BEDS',

'IC_DIS': 'INTERMEDIATE_CARE_DISCHARGES',

'IC_BED_LIC': 'INTERMEDIATE_CARE_LIC_BEDS',

'IC_CENS_DAY': 'INTERMEDIATE_CARE_CEN_DAYS',

'IC_LICBED_DAY': 'INTERMEDIATE_CARE_LIC_BED_DAYS',

'IC_DEV_DISBL_DIS': 'INTERMEDIATE_CARE_DEV_DIS_DISCHARGES',

'IC_DEV_DISBL_BED_LIC': 'INTERMEDIATE_CARE_DEV_DIS_LIC_BEDS',

'IC_DEV_DISBL_LICBED_DAY': 'INTERMEDIATE_CARE_DEV_DIS_LIC_BED_DAYS',

'IC_DEV_DISBL_CENS_DAY': 'INTERMEDIATE_CARE_DEV_DIS_CEN_DAYS',

'HOSP_BED_LIC_TOTL': 'TOT_LIC_BEDS',

'HOSP_CENS_DAY_TOTL': 'TOT_CEN_DAYS',

'HOSP_LICBED_DAY_TOTL': 'TOT_LIC_BED_DAYS',

'HOSP_DIS_TOTL': 'TOT_DISCHARGES',

'CHEM_GAC_CENS_DAY': 'GAC_CDRS_CEN_DAYS',

'CHEM_GAC_BED_LIC': 'GAC_CDRS_LIC_BEDS',

'CHEM_GAC_DIS': 'GAC_CDRS_DISCHARGES',

'CHEM_PSY_CENS_DAY': 'ACUTE_PSYCH_CEN_DAYS',

'CHEM_PSY_DIS': 'ACUTE_PSYCH_DISCHARGES',

'CHEM_PSY_BED_LIC': 'ACUTE_PSYCH_LIC_BEDS',

'NEWBORN_NURSRY_BASSINETS': 'NEWBORN_NURSERY_BASSINETS',

'NEWBORN_NURSRY_INFANTS': 'NEWBORN_NURSERY_INFANTS',

'NEWBORN_NURSRY_CENS_DAY': 'NEWBORN_NURSERY_CEN_DAYS',

'BED_SWING_SN': 'GEN_ACUTE_CARE_SN_SWING_BEDS',

'PSY_LCK_CENS_PATIENT': 'ACUTE_PSYCHIATRIC_PATS_LOCKED_ON_1231',

'PSY_OPN_CENS_PATIENT': 'ACUTE_PSYCHIATRIC_PATS_OPEN_ON_1231',

'PSY_CENS_PATIENT_TOTL': 'ACUTE_PSYCHIATRIC_PATS_TOT_BY_PAYOR',

'PSY_CENS_PATIENT_<=17': 'ACUTE_PSYCHIATRIC_PATS_0_TO_17_ON_1231',

'PSY_CENS_PATIENT_18-64': 'ACUTE_PSYCHIATRIC_PATS_18_TO_64_ON_1231',

'PSY_CENS_PATIENT_=65': 'ACUTE_PSYCHIATRIC_PATS_65_AND_UP_ON_1231',

'PSY_CENS_PATIENT_MCAR': 'ACUTE_PSYCHIATRIC_PATS_MED_TRAD_ON_1231',

'PSY_CENS_PATIENT_MNG_MCAR': 'ACUTE_PSYCHIATRIC_PATS_MED_MANAGED_CARE_ON_1231',

'PSY_CENS_PATIENT_MCAL': 'ACUTE_PSYCHIATRIC_PATS_MED_CAL_TRAD_ON_1231',

'PSY_CENS_PATIENT_MNG_MCAL': 'ACUTE_PSYCHIATRIC_PATS_MED_CAL_MANAGED_CARE_ON_1231',

'PSY_CENS_PATIENT_CO_INDIG': 'ACUTE_PSYCHIATRIC_PATS_COUNTY_INDIGENT_PROG',

'PSY_CENS_PATIENT_OTHR_THIRDPTY': 'ACUTE_PSYCHIATRIC_PATS_3RD_PARTIES_TRAD',

'PSY_CENS_PATIENT_MNG_OTHR_THIRDPTY': 'ACUTE_PSYCHIATRIC_PATS_3RD_PARTIES_MANAGED_CARE',

'PSY_CENS_PATIENT_SHDOYL': 'ACUTE_PSYCHIATRIC_PATS_SHORT_DOYLE',

'PSY_CENS_PATIENT_OTHR_INDIG': 'ACUTE_PSYCHIATRIC_PATS_OTHER_INDIGENT',

'PSY_CENS_PATIENT_OTHR_PAYER': 'ACUTE_PSYCHIATRIC_PATS_OTHER_PAYERS',

'PSY_PROG_SHDOYL': 'SHORT_DOYLE_SERVICES_OFFERED',

'HOSPICE_PROG': 'INPATIENT_HOSPICE_PROG_OFFERED',

'HOSPICE_CLASS_GAC_BED': 'BED_CLASS_GEN_ACUTE_CARE_SERVICE',

'HOSPICE_CLASS_SN_BED': 'BED_CLASS_SN_HOSPICE_SERVICE',

'HOSPICE_CLASS_IC_BED': 'BED_CLASS_IC_HOSPICE_SERVICE',

'INPATIENT_PALLIATIVE_CARE_PROG_OFFERED': 'INPATIENT_PALLIATIVE_CARE_PROG_OFFERED',

'INPATIENT_PALLIATIVE_CARE_PROG_NURSES': 'INPATIENT_PALLIATIVE_CARE_PROG_NURSES',

'INPATIENT_PALLIATIVE_CARE_PROG_NURSES_CERTIFIED': 'INPATIENT_PALLIATIVE_CARE_PROG_NURSES_CERTIFIED',

'INPATIENT_PALLIATIVE_CARE_PROG_PHYSICIAN': 'INPATIENT_PALLIATIVE_CARE_PROG_PHYSICIAN',

'INPATIENT_PALLIATIVE_CARE_PROG_PHYSICIAN_CERTIFIED': 'INPATIENT_PALLIATIVE_CARE_PROG_PHYSICIAN_CERTIFIED',

'INPATIENT_PALLIATIVE_CARE_PROG_SOCIAL_WORKER': 'INPATIENT_PALLIATIVE_CARE_PROG_SOCIAL_WORKER',

'INPATIENT_PALLIATIVE_CARE_PROG_SOCIAL_WORKER_CERTIFIED': 'INPATIENT_PALLIATIVE_CARE_PROG_SOCIAL_WORKER_CERTIFIED',

'INPATIENT_PALLIATIVE_CARE_PROG_CHAPLAINS': 'INPATIENT_PALLIATIVE_CARE_PROG_CHAPLAINS',

'OUTPATIENT_PALLIATIVE_CARE_SERV_OFFERED': 'OUTPATIENT_PALLIATIVE_CARE_SERV_OFFERED',

'EMSA_TRAUMA_CTR_DESIG': 'EMSA_TRAUMA_DESIGNATION',

'EMSA_TRAUMA_PEDS_CTR_DESIG': 'EMSA_TRAUMA_DESIGNATION_PEDIATRIC',

'ED_LIC_LEVL_END': 'LIC_ED_LEV_END',

'ED_LIC_LEVL_BEGIN': 'LIC_ED_LEV_BEGIN',

'ED_ANESTH_AVAIL24HRS': 'AVAIL_SERVICES_ANESTHESIOLOGIST_24HR',

'ED_ANESTH_AVAIL_ON_CALL': 'AVAIL_SERVICES_ANESTHESIOLOGIST_ON_CALL',

'ED_LAB_SVCS_AVAIL24HRS': 'AVAIL_SERVICES_LAB_24HR',

'ED_LAB_SVCS_AVAIL_ON_CALL': 'AVAIL_SERVICES_LAB_ON_CALL',

'ED_OP_RM_AVAIL_ON_CALL': 'AVAIL_SERVICES_OPER_RM_ON_CALL',

'ED_OP_RM_AVAIL24HRS': 'AVAIL_SERVICES_OPER_RM_24HR',

'ED_PHARM_AVAIL24HRS': 'AVAIL_SERVICES_PHARMACIST_24HR',

'ED_PHARM_AVAIL_ON_CALL': 'AVAIL_SERVICES_PHARMACIST_ON_CALL',

'ED_PHYSN_AVAIL24HRS': 'AVAIL_SERVICES_PHYSICIAN_24HR',

'ED_PHYSN_AVAIL_ON_CALL': 'AVAIL_SERVICES_PHYSICIAN_ON_CALL',

'ED_PSYCH_ER_AVAIL24HRS': 'AVAIL_SERVICES_PSYCHIATRIC_ER_24HR',

'ED_PSYCH_ER_AVAIL_ON_CALL': 'AVAIL_SERVICES_PSYCHIATRIC_ER_ON_CALL',

'ED_RADIOL_SVCS_AVAIL_ON_CALL': 'AVAIL_SERVICES_RADIOLOGY_ON_CALL',

'ED_RADIOL_SVCS_AVAIL24HRS': 'AVAIL_SERVICES_RADIOLOGY_24HR',

'EMS_VISITS_NON_URGENT_ADMITTED': 'EMS_VISITS_NON_URGENT_ADMITTED',

'EMS_VISITS_NON_URGENT_NOT_ADMITTED': 'EMS_VISITS_NON_URGENT_TOT',

'EMS_VISITS_URGENT_ADMITTED': 'EMS_VISITS_URGENT_ADMITTED',

'EMS_VISITS_URGENT_NOT_ADMITTED': 'EMS_VISITS_URGENT_TOT',

'EMS_VISITS_MODERATE_ADMITTED': 'EMS_VISITS_MODERATE_ADMITTED',

'EMS_VISITS_MODERATE_NOT_ADMITTED': 'EMS_VISITS_MODERATE_TOT',

'EMS_VISITS_SEVERE_ADMITTED': 'EMS_VISITS_SEVERE_ADMITTED',

'EMS_VISITS_SEVERE_NOT_ADMITTED': 'EMS_VISITS_SEVERE_TOT',

'EMS_VISITS_CRITICAL_NOT_ADMITTED': 'EMS_VISITS_CRITICAL_TOT',

'EMS_VISITS_CRITICAL_ADMITTED': 'EMS_VISITS_CRITICAL_ADMITTED',

'EMS_NO_ADM_VIS_TOTL': 'EMER_DEPT_VISITS_NOT_RESULT_ADMISSIONS_TOT',

'ED_TRAFFIC_TOTL': 'ER_TRAFFIC_TOT',

'EMS_ADM_VIS_TOTL': 'ADMITTED_FROM_EMER_DEPT_TOT',

'EMS_STATION': 'EMER_MED_TREAT_STATIONS_ON_1231',

'EMS_NON_EMERG_VIS': 'NON_EMER_VISITS_IN_EMER_DEPT',

'EMS_REGISTERS_NO_TREAT': 'EMER_REGISTRATIONS_PATS_LEAVE_WO_BEING_SEEN',

'EMS_AMB_DIVERS': 'EMER_DEPT_AMBULANCE_DIVERSION_HOURS',

'EMS_AMB_DIVERS_JAN_HOURS': 'EMER_DEPT_HR_DIVERSION_JAN',

'EMS_AMB_DIVERS_FEB_HOURS': 'EMER_DEPT_HR_DIVERSION_FEB',

'EMS_AMB_DIVERS_MAR_HOURS': 'EMER_DEPT_HR_DIVERSION_MAR',

'EMS_AMB_DIVERS_APR_HOURS': 'EMER_DEPT_HR_DIVERSION_APR',

'EMS_AMB_DIVERS_MAY_HOURS': 'EMER_DEPT_HR_DIVERSION_MAY',

'EMS_AMB_DIVERS_JUN_HOURS': 'EMER_DEPT_HR_DIVERSION_JUN',

'EMS_AMB_DIVERS_JUL_HOURS': 'EMER_DEPT_HR_DIVERSION_JUL',

'EMS_AMB_DIVERS_AUG_HOURS': 'EMER_DEPT_HR_DIVERSION_AUG',

'EMS_AMB_DIVERS_SEP_HOURS': 'EMER_DEPT_HR_DIVERSION_SEP',

'EMS_AMB_DIVERS_OCT_HOURS': 'EMER_DEPT_HR_DIVERSION_OCT',

'EMS_AMB_DIVERS_NOV_HOURS': 'EMER_DEPT_HR_DIVERSION_NOV',

'EMS_AMB_DIVERS_DEC_HOURS': 'EMER_DEPT_HR_DIVERSION_DEC',

'EMS_AMB_DIVERS_TOTL_HOURS': 'EMER_DEPT_HR_DIVERSION_TOT',

'OP_RM_MIN_IP': 'INPATIENT_SURG_OPER_RM_MINS',

'SURG_IP': 'INPATIENT_SURG_OPER',

'SURG_OP': 'OUTPATIENT_SURG_OPER',

'OP_RM_MIN_OP': 'OUTPATIENT_SURG_OPER_RM_MINS',

'OP_RM_IP_ONLY': 'INPAT_OPER_RM',

'OP_RM_OP_ONLY': 'OUTPAT_OPER_RM',

'OP_RM_IP_AND_OP': 'INPAT_OUTPAT_OPER_RM',

'OP_RM_TOTL': 'OPER_RM_TOT',

'AMB_SURG_PROG': 'OFFER_AMBULATORY_SURG_PROG',

'BIRTHS_LIVE_TOTL': 'LIVE_BIRTHS_TOT',

'BIRTHS_LIVE_<5LBS_8OZ': 'LIVE_BIRTHS_LT_2500GM',

'BIRTHS_LIVE_<3LBS_5OZ': 'LIVE_BIRTHS_LT_1500GM',

'ABC_OP_PROG': 'OFFER_ALTERNATE_BIRTH_PROG',

'ABC_LDR': 'ALTERNATE_SETTING_LDR',

'ABC_LDRP': 'ALTERNATE_SETTING_LDRP',

'BIRTHS_LIVE_ABC': 'LIVE_BIRTHS_IN_ALTERNATIVE_SETTING',

'BIRTHS_LIVE_C_SEC': 'LIVE_BIRTHS_C_SECTION',

'LICENSURE_CVSURG_SVCS': 'LIC_CARDIOLOGY_CARDIOVASCULAR_SURG_SERVICES',

'CVSURG_LIC_OP_RM': 'CARDIOVASCULAR_OPER_RM',

'CVSURG_WITH_ECBPASS_PED': 'CARDIOVASCULAR_SURG_OPER_PEDIATRIC_BYPASS_USED',

'CVSURG_WITHOUT_ECBPASS_PED': 'CARDIOVASCULAR_SURG_OPER_PEDIATRIC_BYPASS_NOT_USED',

'CVSURG_WITHOUT_ECBPASS_ADLT': 'CARDIOVASCULAR_SURG_OPER_ADULT_BYPASS_NOT_USED',

'CVSURG_WITH_ECBPASS_ADLT': 'CARDIOVASCULAR_SURG_OPER_ADULT_BYPASS_USED',

'CVSURG_WITHOUT_ECBPASS_TOTL': 'CARDIOVASCULAR_SURG_OPER_BYPASS_NOT_USED_TOT',

'CVSURG_WITH_ECBPASS_TOTL': 'CARDIOVASCULAR_SURG_OPER_BYPASS_USED_TOT',

'CVSURG_CABG_TOTL': 'CORONARY_ARTERY_BYPASS_GRAFT_SURG',

'CATH_CARD_RM': 'CARDIAC_CATHETERIZATION_LAB_RM',

'CATH_IP_PED_THER_VIS': 'CARD_CATH_PED_IP_THER_VST',

'CATH_IP_PED_DX_VIS': 'CARD_CATH_PED_IP_DIAG_VST',

'CATH_OP_PED_THER_VIS': 'CARD_CATH_PED_OP_THER_VST',

'CATH_OP_PED_DX_VIS': 'CARD_CATH_PED_OP_DIAG_VST',

'CATH_IP_ADLT_DX_VIS': 'CARDIAC_CATHETERIZATION_ADULT_INPAT_DIAGNOSTIC_VISITS',

'CATH_IP_ADLT_THER_VIS': 'CARDIAC_CATHETERIZATION_ADULT_INPAT_THERAPEUTIC_VISITS',

'CATH_OP_ADLT_THER_VIS': 'CARDIAC_CATHETERIZATION_ADULT_OUTPAT_THERAPEUTIC_VISITS',

'CATH_OP_ADLT_DX_VIS': 'CARDIAC_CATHETERIZATION_ADULT_OUTPAT_DIAGNOSTIC_VISITS',

'CATH_THER_VIS_TOTL': 'CARDIAC_CATHETERIZATION_THERAPEUTIC_VISITS_TOT',

'CATH_DX_VIS_TOTL': 'CARDIAC_CATHETERIZATION_DIAGNOSTIC_VISITS_TOT',

'CARDIAC_CATH_DX_PROC': 'DIAGNOSTIC_CARDIAC_CATH_PROC',

'MYOCARDIAL_BIOPSY': 'MYOCARDIAL_BIOPSY',

'PACEMKR_PERM_IMPL': 'PERM_PACEMAKER_IMPLANT',

'OTH_PERM_PACEMAKER_PROC': 'OTH_PERM_PACEMAKER_PROC',

'ICD_IMPLANTATION': 'IMPLANABLE_CARDIO_DEFIB_IMPLANTATION',

'OTH_ICD_PROCEDURES': 'OTH_PROCEDURES',

'PCI_WITH_STENT': 'PCI_WITH_STENT',

'PCI_WITHOUT_STENT': 'PCI_WO_STENT',

'ATHERECTOMY_PTCRA': 'ATHERECTOMY',

'THROMBO_AGT': 'THROMBOLYTIC_AGENTS',

'PTBV': 'PTBV',

'DX_EP_STUDY': 'DIAGNOSTIC_ELECTROPHYSIOLOGY_EP',

'CATHETER_ABLATION': 'CATHETER_ABLATION',

'PERIPHERAL_VASCULAR_ANGIOGRAPHY': 'PERIPHERAL_VASCULAR_ANGIOGRAPHY',

'PERIPHERAL_VASCULAR_INTERVENTIONAL': 'PERIPHERAL_VASCULAR_INTERVENTIONAL',

'CAROTID_STENTING': 'CAROTID_STENTING',

'INTRA_AORTIC_BALLOON_PUMP_INS': 'INTRA_AORTIC_BALLOON_PUMP_INSERTION',

'CATHETER_BASED_VENTRICULAR_INS': 'CATHETER_BASED_VENTRICULAR_ASSIST_DEVICE_INSERTION',

'OTHR_CATH_PROC': 'ALL_OTHER_CATHETERIZATION_PROC',

'CATH_TOTL': 'CATHETERIZATION_PROC_TOT',

'EQUIP_ACQ_OVER_500K': 'FAC_ACQUIRE_EQUIP_OVER_500K',

'EQUIP_01_ACQUI_DT': 'DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_01',

'EQUIP_01_VALUE': 'EQUIP_VAL_01',

'EQUIP_01_ACQUI_MEANS': 'MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_01',

'EQUIP_01_DESCRIP': 'DESC_EQUIP_01',

'EQUIP_02_DESCRIP': 'DESC_EQUIP_02',

'EQUIP_02_ACQUI_MEANS': 'MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_02',

'EQUIP_02_ACQUI_DT': 'DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_02',

'EQUIP_02_VALUE': 'EQUIP_VAL_02',

'EQUIP_03_VALUE': 'EQUIP_VAL_03',

'EQUIP_03_ACQUI_DT': 'DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_03',

'EQUIP_03_ACQUI_MEANS': 'MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_03',

'EQUIP_03_DESCRIP': 'DESC_EQUIP_03',

'EQUIP_04_DESCRIP': 'DESC_EQUIP_04',

'EQUIP_04_ACQUI_MEANS': 'MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_04',

'EQUIP_04_ACQUI_DT': 'DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_04',

'EQUIP_04_VALUE': 'EQUIP_VAL_04',

'EQUIP_05_VALUE': 'EQUIP_VAL_05',

'EQUIP_05_ACQUI_DT': 'DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_05',

'EQUIP_05_ACQUI_MEANS': 'MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_05',

'EQUIP_05_DESCRIP': 'DESC_EQUIP_05',

'EQUIP_06_ACQUI_MEANS': 'MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_06',

'EQUIP_06_ACQUI_DT': 'DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_06',

'EQUIP_06_DESCRIP': 'DESC_EQUIP_06',

'EQUIP_06_VALUE': 'EQUIP_VAL_06',

'EQUIP_07_VALUE': 'EQUIP_VAL_07',

'EQUIP_07_ACQUI_DT': 'DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_07',

'EQUIP_07_ACQUI_MEANS': 'MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_07',

'EQUIP_07_DESCRIP': 'DESC_EQUIP_07',

'EQUIP_08_DESCRIP': 'DESC_EQUIP_08',

'EQUIP_08_ACQUI_MEANS': 'MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_08',

'EQUIP_08_ACQUI_DT': 'DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_08',

'EQUIP_08_VALUE': 'EQUIP_VAL_08',

'EQUIP_09_VALUE': 'EQUIP_VAL_09',

'EQUIP_09_ACQUI_DT': 'DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_09',

'EQUIP_09_ACQUI_MEANS': 'MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_09',

'EQUIP_09_DESCRIP': 'DESC_EQUIP_09',

'EQUIP_10_DESCRIP': 'DESC_EQUIP_10',

'EQUIP_10_ACQUI_MEANS': 'MEANS_FOR_ACQUISITION_10',

'EQUIP_10_ACQUI_DT': 'DT_AQUIRE_EQUIP_10',

'EQUIP_10_VALUE': 'EQUIP_VAL_10',

'CAP_EXP_OVER_1MIL': 'PROJ_OVER_1M',

'PROJ_01_PROJTD_CAP_EXP': 'PROJ_EXPENDITURES_01',

'PROJ_01_OSHPD_PROJ_NO': 'OSHPD_PROJ_NO_01',

'PROJ_01_DESCRIP_CAP_EXP': 'DESC_PROJ_01',

'PROJ_02_DESCRIP_CAP_EXP': 'DESC_PROJ_02',

'PROJ_02_OSHPD_PROJ_NO': 'OSHPD_PROJ_NO_02',

'PROJ_02_PROJTD_CAP_EXP': 'PROJ_EXPENDITURES_02',

'PROJ_03_OSHPD_PROJ_NO': 'OSHPD_PROJ_NO_03',

'PROJ_03_PROJTD_CAP_EXP': 'PROJ_EXPENDITURES_03',

'PROJ_03_DESCRIP_CAP_EXP': 'DESC_PROJ_03',

'PROJ_04_DESCRIP_CAP_EXP': 'DESC_PROJ_04',

'PROJ_04_OSHPD_PROJ_NO': 'OSHPD_PROJ_NO_04',

'PROJ_04_PROJTD_CAP_EXP': 'PROJ_EXPENDITURES_04',

'PROJ_05_OSHPD_PROJ_NO': 'OSHPD_PROJ_NO_05',

'PROJ_05_PROJTD_CAP_EXP': 'PROJ_EXPENDITURES_05',

'PROJ_05_DESCRIP_CAP_EXP': 'DESC_PROJ_05'}

We can now define a new version of the read_hospital_data function that uses

the crosswalk to change the column names when year < 2018. You can use the

dict .get method, which tries to get the value for the key in its first

argument and returns its second argument if that key isn’t in the dict. Let’s

also change function to exclude columns with ALOS in the name, because they

have no equivalent in the pre-2018 files:

def read_hospital_data(path, year):

# Read the 2nd sheet of the file.

sheet = pl.read_excel(path, sheet_id=2)

# Remove the first 4 and last row.

sheet = sheet[4:-1, :]

# Fix pre-2018 column names.

if year < 2018:

sheet.columns = [cwalk.get(c, c) for c in sheet.columns]

# Select only a few columns of interest.

facility_cols = pl.col(

"FAC_NAME", "FAC_CITY", "FAC_ZIP", "FAC_OPERATED_THIS_YR",

"FACILITY_LEVEL", "TEACH_HOSP", "COUNTY", "PRIN_SERVICE_TYPE",

)

sheet = sheet.select(

pl.lit(year).alias("year"),

facility_cols,

pl.col("^TOT.*$", "^.*RESPIRATORY.*$")

.exclude("^.*ALOS.*$")

.cast(pl.Float64),

)

# Rename the columns to lowercase.

sheet = sheet.rename(str.lower)

return sheet

Now we can test the function on all of the files. This time, we’ll check that

hosps = []

for path in paths:

year = get_hospital_year(path)

hosp = read_hospital_data(path, year)

hosps.append(hosp)

len(hosps)

8

You can use the pl.concat function to concatenate, or stack, a list of data

frames:

hosps = pl.concat(hosps)

hosps.head()

| year | fac_name | fac_city | fac_zip | fac_operated_this_yr | facility_level | teach_hosp | county | prin_service_type | tot_lic_beds | tot_lic_bed_days | tot_discharges | tot_cen_days | acute_respiratory_care_lic_beds | acute_respiratory_care_lic_bed_days | acute_respiratory_care_discharges | acute_respiratory_care_intra_transfers | acute_respiratory_care_cen_days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i32 | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 |

| 2021 | "ALAMEDA HOSPITAL" | "ALAMEDA" | "94501" | "Yes" | "Parent Facility" | "No" | "Alameda" | "General Medical / Surgical" | 247.0 | 90155.0 | 2431.0 | 66473.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | null | null | null |

| 2021 | "ALTA BATES SUMMIT MEDICAL CENT… | "BERKELEY" | "94705" | "Yes" | "Parent Facility" | "No" | "Alameda" | "General Medical / Surgical" | 339.0 | 123735.0 | 11344.0 | 53710.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | null | null | null |

| 2021 | "UCSF BENIOFF CHILDREN'S HOSPIT… | "OAKLAND" | "94609" | "Yes" | "Parent Facility" | "No" | "Alameda" | "Pediatric" | 215.0 | 78475.0 | 7256.0 | 38381.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | null | null | null |

| 2021 | "FAIRMONT HOSPITAL" | "SAN LEANDRO" | "94578" | "Yes" | "Consolidated Facility" | "No" | "Alameda" | "Long-Term Care (SN / IC)" | 109.0 | 39785.0 | 179.0 | 38652.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | null | null | null |

| 2021 | "ALTA BATES SUMMIT MEDICAL CENT… | "BERKELEY" | "94704" | "Yes" | "Consolidated Facility" | "No" | "Alameda" | "Psychiatric" | 68.0 | 24820.0 | 2236.0 | 19950.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | null | null | null |

We’ve finally got all of the data in a single data frame!

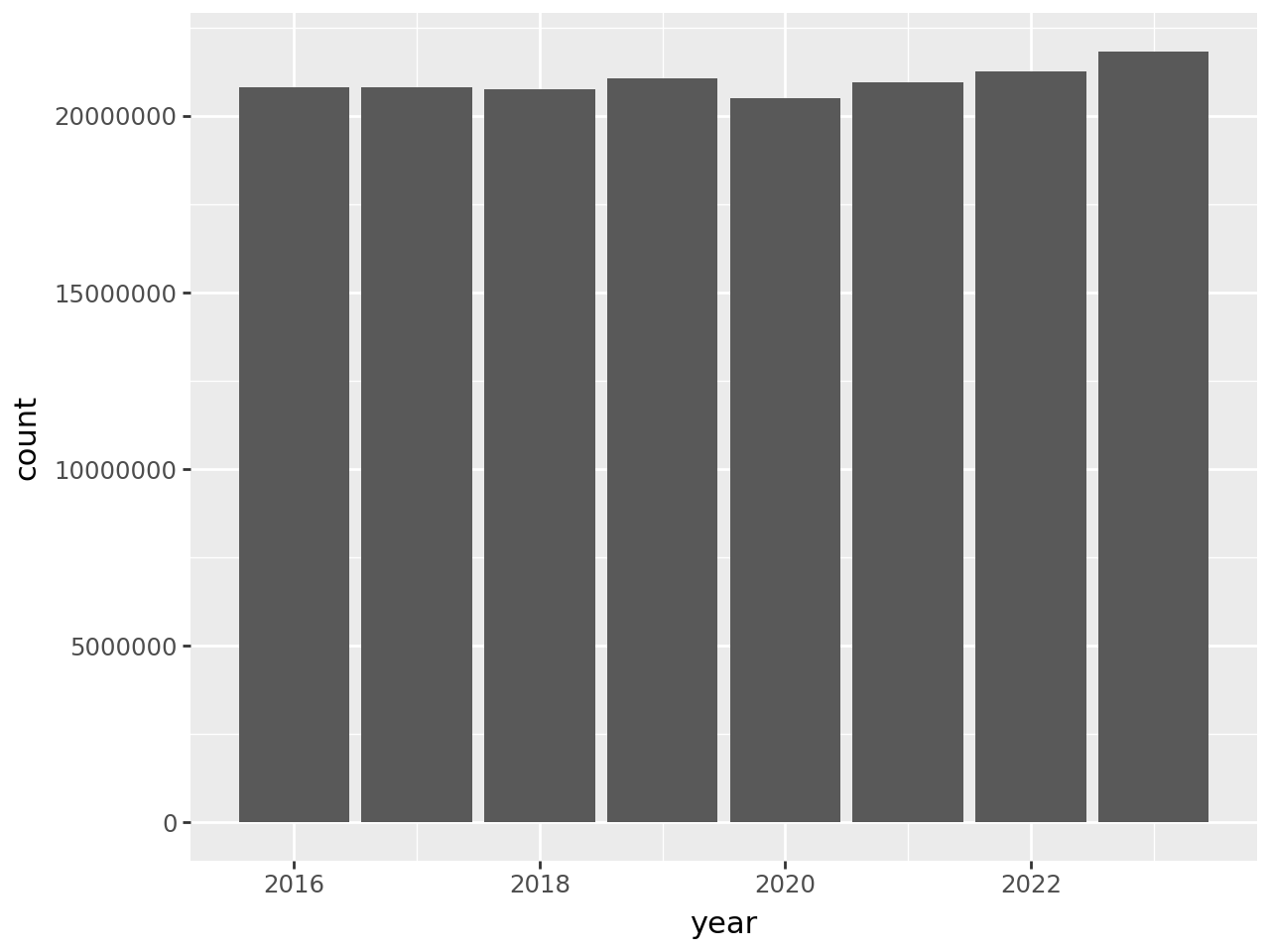

To begin to address whether hospital utilization changed in 2020, let’s make a bar plot of total census-days:

According to the plot, total census-days was slightly lower in 2020 than in

2019. This is a bit surprising, but it’s possible that California hospitals

typically operate close to maximum capacity and were not able to substantially

increase the number of beds in 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. You

can use other columns in the data set, such as tot_lic_beds or

tot_lic_bed_days, to check this.

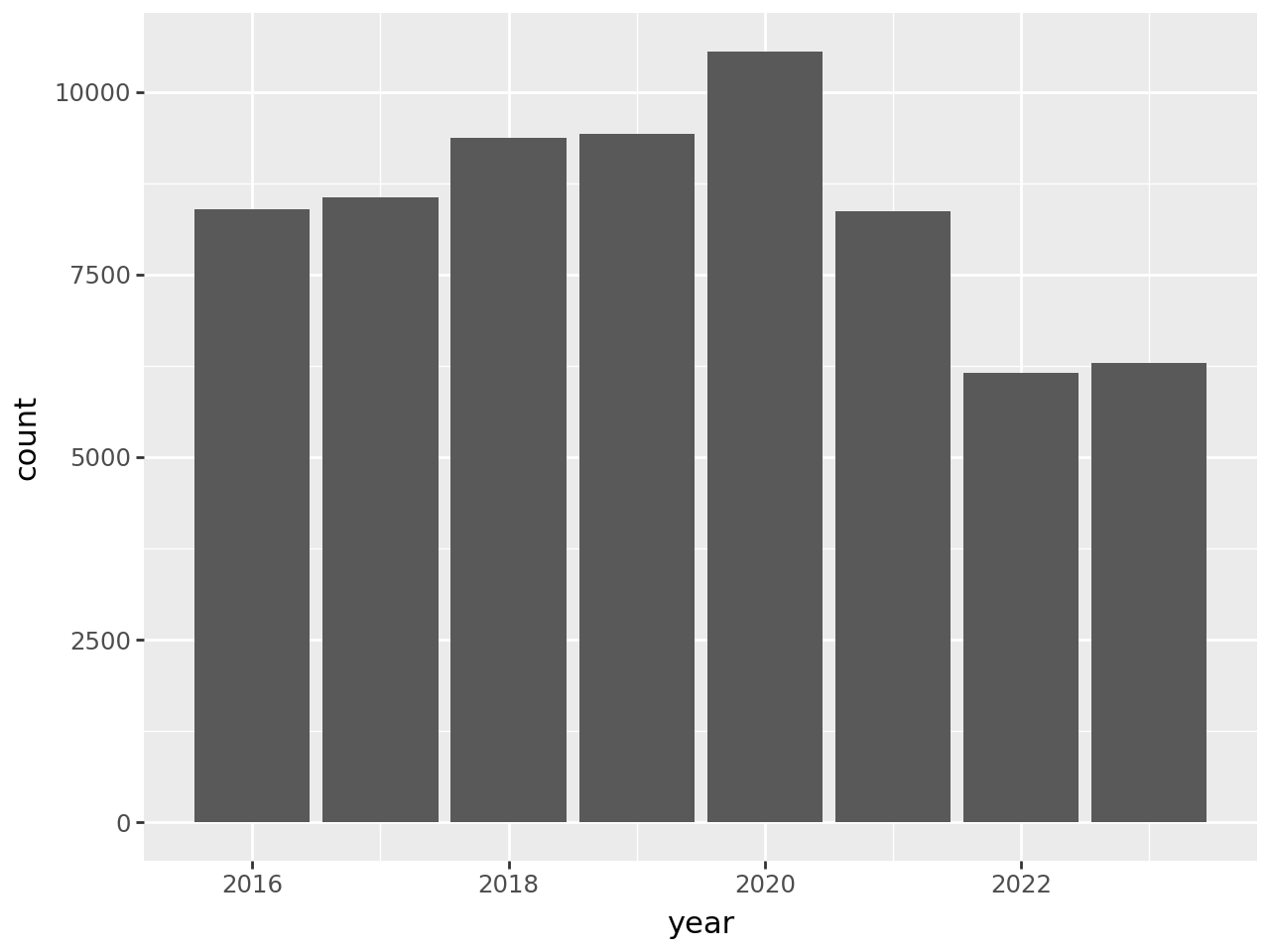

Let’s also look at census-days for acute respiratory care:

In this plot, there’s a clear uptick in census-days in 2020, and then an interesting decrease to below 2019 levels in the years following. Again, you could use other columns in the data set to investigate this further. We’ll end this case study here, having accomplished the difficult task of reading the data and the much easier task of doing a cursory preliminary analysis of the data.

4.5. Exercises#

4.5.1. Exercise 1#

Try writing a function is_leap that detects leap years. The input to your

function should be an integer year (or a series of years), and the output

should be a Boolean value. A year is a leap year if either of these conditions

is true:

It is divisible by 4 and not 100

It is divisible by 400

That means the years 2004 and 2000 are leap years, but the year 2200 is not.

Hint: The modulo operator % returns the remainder after divding a number, so

for example 4 % 3 returns 1.

Here’s a few test cases for your function:

is_leap(400)

is_leap(1997)