3 Browsing Files

After this lesson, you should be able to:

- Define file system, directory, and path

- Write paths to files or directories

- Explain what a working directory is

- In the CLI:

- Print and change the shell’s working directory

- Print the contents of a directory

- Create and remove directories

A key feature of the CLI is that you can browse through and inspect the files and directories on your computer. With GUIs, we tend to navigate with our mouses; on the command line, we’ll use our keyboard. This chapter begins with some background information and vocabulary about how computers organize files, then gives a hands-on introduction to working with files and directories in the CLI.

3.1 File Systems

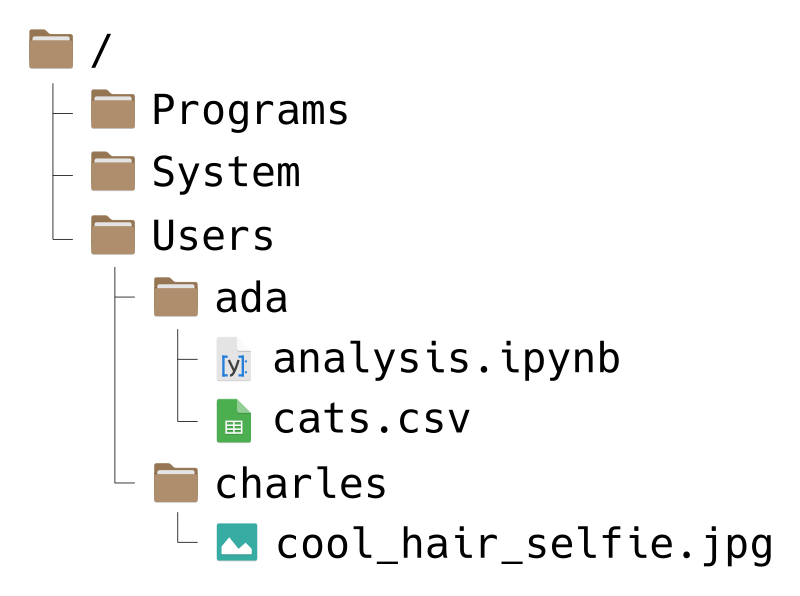

Your computer’s file system consists of files (chunks of data) and directories (or “folders”) to organize those files. For instance, the file system on a computer shared by Ada and Charles, two pioneers of computing, might look like this:

Don’t worry if your file system looks a bit different from the picture.

File systems have a tree-like structure, with a top-level directory called the root directory. On Ada and Charles’ computer, the root is called /, which is also what it’s called on all macOS and Linux computers. On Windows, the root is usually called C:/, but sometimes other letters, like D:/, are also used depending on the computer’s hardware.

A path is a list of directories that leads to a specific file or directory on a file system (imagine giving directions to someone as they walk through the file system). Use forward slashes / to separate the directories in a path, rather than commas or spaces. The root directory includes a forward slash as part of its name, and doesn’t need an extra one.

For example, suppose Ada wants to write a path to the file cats.csv. She can write the path like this:

/Users/ada/cats.csvYou can read this path from left-to-right as, “Starting from the root directory, go to the Users directory, then from there go to the ada directory, and from there go to the file cats.csv.” Alternatively, you can read the path from right-to-left as, “The file cats.csv inside of the ada directory, which is inside of the Users directory, which is in the root directory.”

As another example, suppose Charles wants a path to the Programs directory. He can write:

/Programs/The / at the end of this path is reminder that Programs is a directory, not a file. Charles could also write the path like this:

/ProgramsThis is still correct, but it’s not as obvious that Programs is a directory. In other words, when a path leads to a directory, including a trailing slash is optional, but makes the meaning of the path clearer. Paths that lead to files never have a trailing slash.

On Windows computers, the components of a path are usually separated with backslashes \ instead of forward slashes /.

Git Bash is an exception: the shell commands you’ve learned so far expect and understand paths separated with forward slashes. If you instead use Windows’ built-in terminal, you’ll need to use paths separated with backslashes (and a different set of commands).

3.2 Absolute & Relative Paths

A path that starts from the root directory, like all of the ones we’ve seen so far, is called an absolute path. The path is “absolute” because it unambiguously describes where a file or directory is located. The downside is that absolute paths usually don’t work well if you share your code.

For example, suppose Ada uses the path /Programs/ada/cats.csv to load the cats.csv file in her code. If she shares her code with another pioneer of computing, say Gladys, who also has a copy of cats.csv, it might not work. Even though Gladys has the file, she might not have it in a directory called ada, and might not even have a directory called ada on her computer. Because Ada used an absolute path, her code works on her own computer, but isn’t portable to others.

On the other hand, a relative path is one that doesn’t start from the root directory. The path is “relative” to an unspecified starting point, which usually depends on the context.

For instance, suppose Ada’s code is saved in the file analysis.ipynb, which is in the same directory as cats.csv on her computer. Then instead of an absolute path, she can use a relative path in her code:

cats.csvThe context is the location of analysis.ipynb, the file that contains the code. In other words, the starting point on Ada’s computer is the ada directory. On other computers, the starting point will be different, depending on where the code is stored.

Now suppose Ada sends her corrected code in analysis.ipynb to Gladys, and tells Gladys to put it in the same directory as cats.csv. Since the path cats.csv is relative, the code will still work on Gladys’ computer, as long as the two files are in the same directory. The name of that directory and its location in the file system don’t matter, and don’t have to be the same as on Ada’s computer. Gladys can put the files in a directory /Users/gladys/from_ada/ and the path (and code) will still work.

Relative paths can include directories. For example, suppose that Charles wants to write a relative path from the Users directory to a cool selfie he took. Then he can write:

charles/cool_hair_selfie.jpgYou can read this path as, “Starting from wherever you are, go to the charles directory, and from there go to the cool_hair_selfie.jpg file.” In other words, the relative path depends on the context of the code or program that uses it.

When you use paths in code, they should almost always be relative paths. This ensures that the code is portable to other computers, which is an important aspect of reproducibility. Another benefit is that relative paths tend to be shorter, making your code easier to read (and write).

When you write paths, there are three shortcuts you can use. These are most useful in relative paths, but also work in absolute paths:

.means the current directory...means the directory above the current directory.~means the home directory. Each user has their own home directory, whose location depends on the operating system and their username. Home directories are typically found insideC:/Users/on Windows,/Users/on macOS, and/home/on Linux.

As an example, suppose Ada wants to write a (relative) path from the ada directory to Charles’ cool selfie. Using these shortcuts, she can write:

../charles/cool_hair_selfie.jpgRead this as, “Starting from wherever you are, go up one directory, then go to the charles directory, and then go to the cool_hair_selfie.jpg file.” Since /Users/ada is Ada’s home directory, she could also write the path as:

~/../charles/cool_hair_selfie.jpgThis path has the same effect, but the meaning is slightly different. You can read it as “Starting from your home directory, go up one directory, then go to the charles directory, and then go to the cool_hair_selfie.jpg file.”

The .. and ~ shortcut are frequently used and worth remembering. The . shortcut is included here in case you see it in someone else’s code. Since it means the current directory, a path like ./cats.csv is identical to cats.csv, and the latter is preferable for being simpler. There are a few specific situations where . is necessary, but they fall outside the scope of this text.

3.3 The Working Directory

Opening a directory with a graphical file browser (such as Explorer or Finder) is probably one of the things you do most frequently on your computer. File browsers generally open one directory at a time and display the contents. The CLI, or more specifically, the shell, works the same way. The shell always has a directory open. This is called the working directory. Think of the working directory as the directory the shell is currently “at” or watching.

Section 3.2 explained that relative paths have a starting point that depends on the context where the path is used. The shell uses the working directory as the starting point for relative paths.

The shell provides commands to manipulate the working directory. The command pwd prints the absolute path for the working directory. It doesn’t require any arguments:

pwd/home/nickOn your computer, the output from pwd will likely be different.

The pwd command is very useful for getting your bearings. Run it any time you’re uncertain about what the working directory is.

If you write a relative path and it doesn’t work as expected, the first thing to do is run pwd to check the working directory.

The related cd command changes the working directory. Without any arguments, it changes the working directory to your home directory. Go ahead and try changing to the home directory and printing its path:

cd

pwd/home/nickYou can change the working directory to a specific directory by putting the path to the directory after the cd command. Go to the directory above the home directory:

cd ..Now print the path again:

pwd/homeThe cd command understands both absolute and relative paths.

Another command that’s useful for dealing with the working directory and file system is ls. The ls command lists the names of all of the files and directories inside of a directory. It accepts a path to a directory as an argument, or assumes the working directory if you don’t pass a path. For instance:

ls /bin dev etc lib lost+found opt root sbin swapfile tmp var

boot efi home lib64 mnt proc run srv sys usr windowslsarchive depot go haven mill notes.md wharf woods ZoteroAs usual, since you have a different computer, you’re likely to see different output if you run this code. If you run ls with an invalid path, the shell emits an error:

ls /this/path/is/fake/"/this/path/is/fake/": No such file or directory (os error 2)3.4 Making & Removing Directories

When you start working on a project (whether it’s academic, personal, or something else), it’s a good habit to make a new directory, called a project directory or repository, where you’ll keep all of the project’s files. This way you can easily find, back up, and share the files.

Give each project directory a descriptive name. This will make it easier for you to find the project in the future. At DataLab, we typically use names that include the year (or date) and title of the project. Use underscores (_) or dashes (-) to separate words and components in the name rather than spaces.

At the command line, you can use the mkdir command to make a directory. Navigate back to your home directory, then use mkdir to make a directory called 2026_intro-cmd:

cd

mkdir 2026_intro-cmdCheck that the new directory is there with the ls command:

ls2026_intro-cmd archive depot go haven mill notes.md wharf woods ZoteroChange to the new directory and check that it’s empty:

cd 2026_intro-cmd

lsYou can make subdirectories to further organize your project directories. Try making a subdirectories called data and figures:

mkdir data

mkdir figures

lsdata figuresSometimes you might make a directory and then decide later that you don’t need it. The rmdir command removes an empty directory. Go ahead and remove the figures directory, since we’re not going to make any figures:

rmdir figuresThe rmdir command will only remove empty directories, so there’s no risk of accidentally removing important files. Later on, we’ll explain how to remove files (and directories that contain files).

3.5 Reference: Browsing Commands

This chapter introduced five different commands you can use to browse files at the command line:

| Command | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

pwd |

Prints the working directory | pwd |

cd |

Changes the working directory | cd; cd my_directory |

ls |

Lists the contents of a directory | ls; ls my_directory |

mkdir |

Makes a new directory | mkdir my_directory |

rmdir |

Removes an empty directory | rmdir my_directory |

Make sure you understand these commands before moving on, since it’s likely you’ll use them more frequently than any others.