2 About GitHub

2.1 The Basics

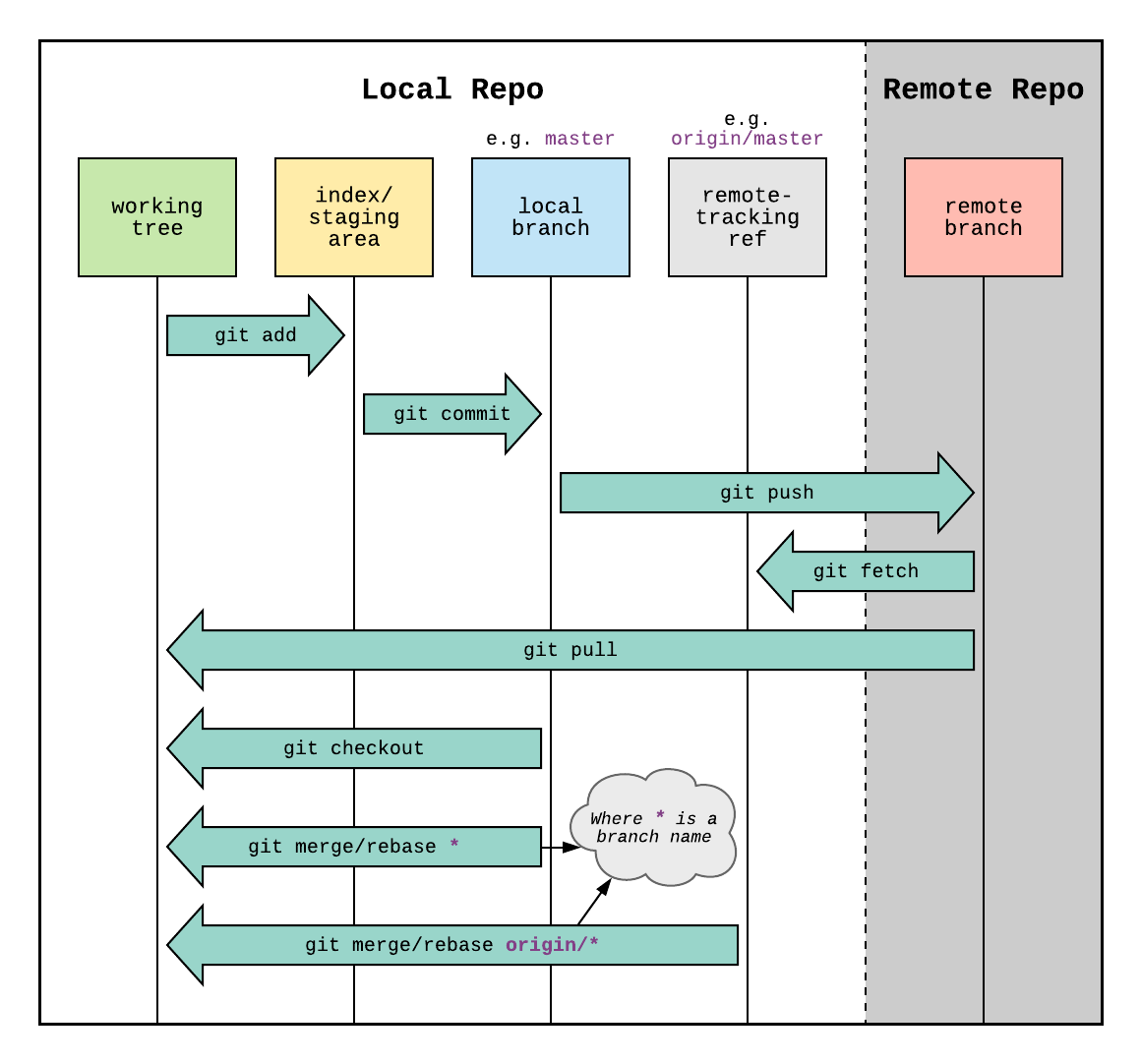

At its simplest, GitHub is a hosting service for Git repositories. Much like Dropbox or Google Drive, it gives you a space to remotely store your code and related files. This can be useful when working on projects that require, for example, some kind of server, whether for the purposes of running large, potentially time-consuming data analyses or for serving up public-facing content (like a website). For such projects, GitHub acts as a reference point with which you can add, or push, changes on one computer and bring them down, or pull them, onto another. The process would look something like the following, where pushing and pulling from a remote branch entails keeping a reference point for a project that you’re developing locally:

With this diagram in mind, it’s not much of a conceptual leap to imagine how two or more people could work from the same remote repository. Each would pull that repository onto their respective local computers, make a branch, implement their changes, and push those changes back to the remote source. That way, multiple parts of a project could be under development simultaneously, and any such changes made to that project would be trackable according to the logic of version control.

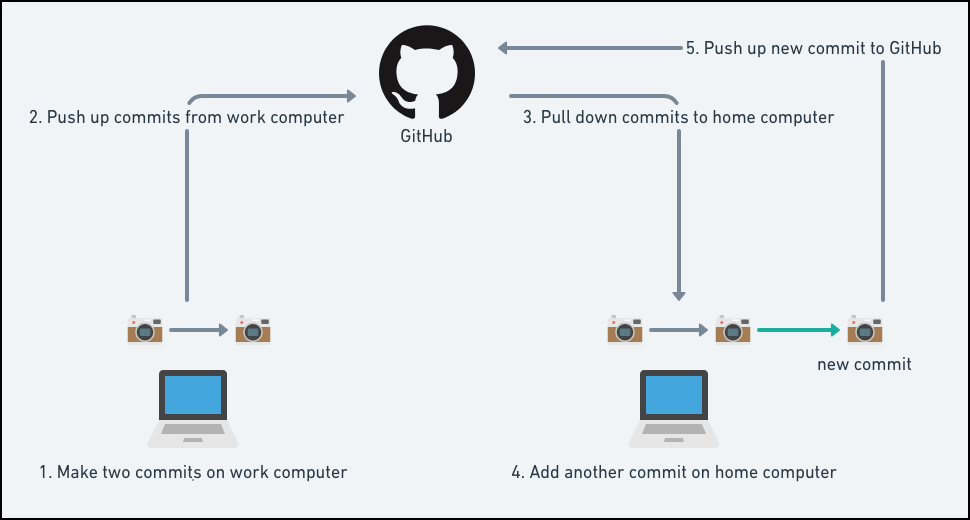

Simultaneously pushing and pulling on multiple computers would look something like the following:

2.2 Communicating Through GitHub

So far, however, this whole process could be implemented with other version control software. What makes GitHub special is the fact that, more than being simply a place to store files, the service is above all a communication channel. Where GitHub extends the functionality of version control is not just where it offers various forms of cloud hosting; it is also where GitHub provides tools that let people talk about the code they’re working on. It’s a place where team members can propose and explain the changes they make, look at changes others have made, track and discuss any bugs that might come up, get feedback from others, and plan for any future changes the team intends to make.

Learning how to use GitHub, then, is as much about learning how to communicate effectively through the different facets of the service as it is about acquainting yourself with new technical skills (i.e., using your computer to track code remotely). In this workshop, we’ll discuss both parts of using the service and do so with an eye toward how GitHub can facilitate team science.

A short summary of the different facets of communication GitHub provides includes:

- Documentation, often through README files

- Issue tracking for bug reporting and assigning tasks

- Pull requests for proposing and discussing changes

- Wikis, which may feature additional documentation, tutorials, etc.

- Project boards for long-term planning

- Various graph visualizations for project overview

Additionally, GitHub users can monitor and modify other projects’ code using “Watch”, “Star”, and “Fork” functionalities. The service also provides teams with the ability to specify licensing information for their projects.

2.3 What Should I Push to GitHub?

A quick word about what should and shouldn’t be pushed to a remote repository, especially with an eye toward what we’ve said about communication. You can, of course, host large data files on GitHub, but there are a few caveats. For one, the site does have a storage limit, and it can also become quite inefficient to have team members constantly push/pull large files to/from GitHub. Further, hosting data files might not be particularly relevant to what a team might need to discuss. Data may change often over the course of a project, but tracking individual observations might not be necessary—more meaningful would be a conversation about how code has made, or might make, such changes. The latter is likely to be something that GitHub is better suited to facilitate.

It’s best, then, to host your data files separately from GitHub, either by way of a remote database or some kind of cloud service like Google Drive. Exceptions may come up, however, so the decision about what to track should ultimately be one made by the team.

Examples of what should be tracked with GitHub:

- Code

- Documentation

- Make files

- Some supporting media (small images, for example)

Finally, note that even though you can set a repository to either “Public” or “Private” (which controls who can see your project), it’s recommended that you refrain from uploading various access credentials (API keys, database passwords, etc.) to GitHub.