4 Pushing a Repository

Now that you’re all set up with GitHub, it’s time to sync the website with a local repository on your computer.

4.1 Making a Test Repository

First, use the command line to make a new directory in your Home folder:

$ mkdir ~/my_first_remote_directoryPut this directory under version control with Git:

$ cd ~/my_first_remote_directory

$ git init

Initialized empty Git repository in <path>/<to>/my_first_remote_directory/.git/Now let’s create a new file, called:

$ echo 'Hello world!' > README.mdTime to add and commit our file with Git. Don’t forget to write a short note in the commit message.

$ git add README.md

$ git commit -m 'Added a README file'

main (root-commit) cad7867] Added a README file

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 README.md4.2 Preparing to Sync Your Repository

So far so good! All we’ve done is repeat the normal workflow for putting files under version control. But now we need to step away from the command line for a moment and prepare a space for receiving this repository on GitHub.

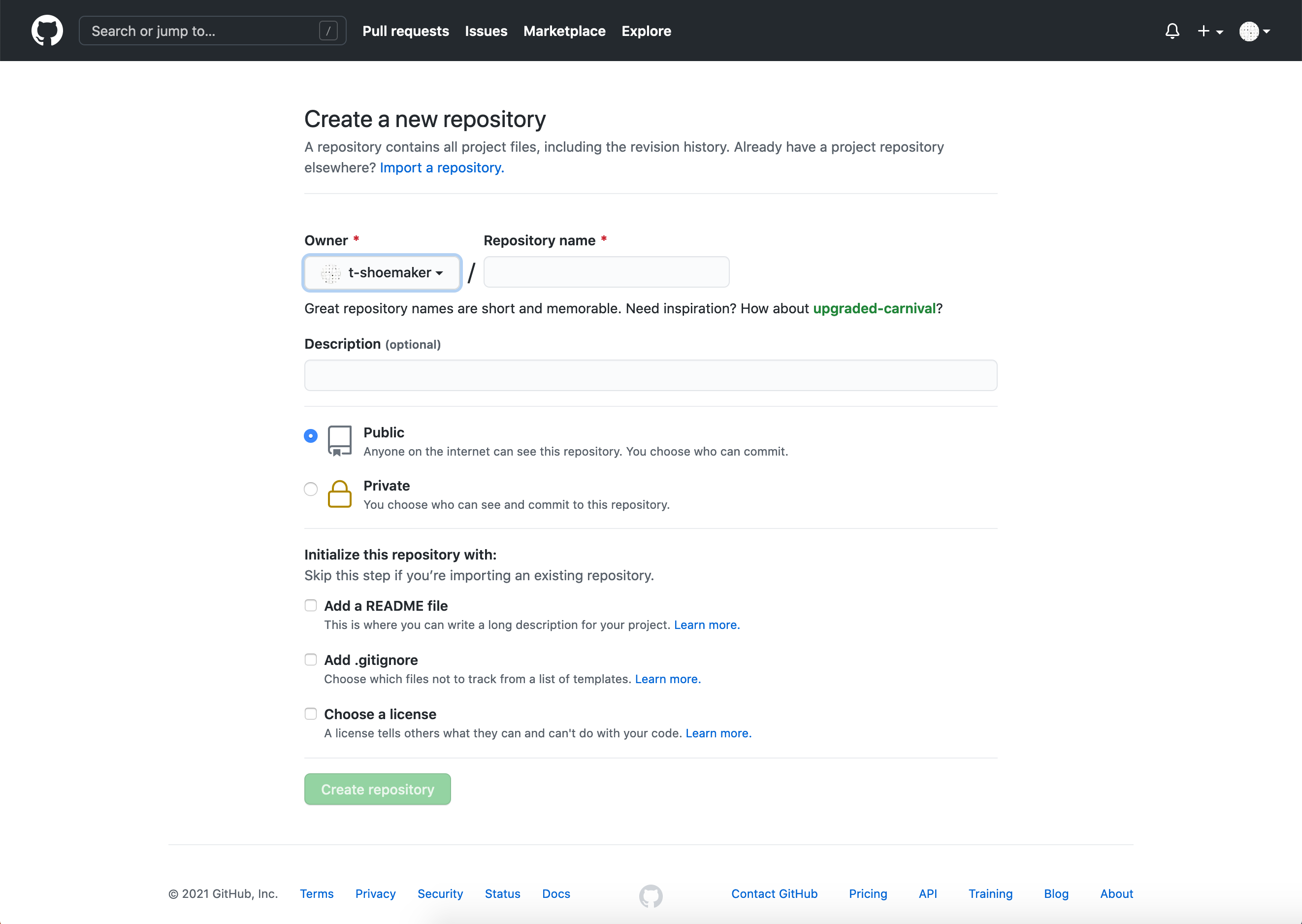

To do so, go to github.com and, on your homepage, click the “Create repository” button. You’ll be taken to this page:

There are a few things of note here:

- Repository name: your repository’s name, which should be the same as what’s on your computer

- Description: a short (1-2 sentence) explanation of what’s in this repository

- Public/private setting: repositories may be either “public” (viewable by anyone) or “private” (only viewable by you and those to whom you grant access)

- Initialize with details, including:

- A README file: a form of documentation; provides information about the files in the repository

- A .gitignore file: instructs Git to ignore specific files or filetypes

- A license: governs the use or redistribution of your files

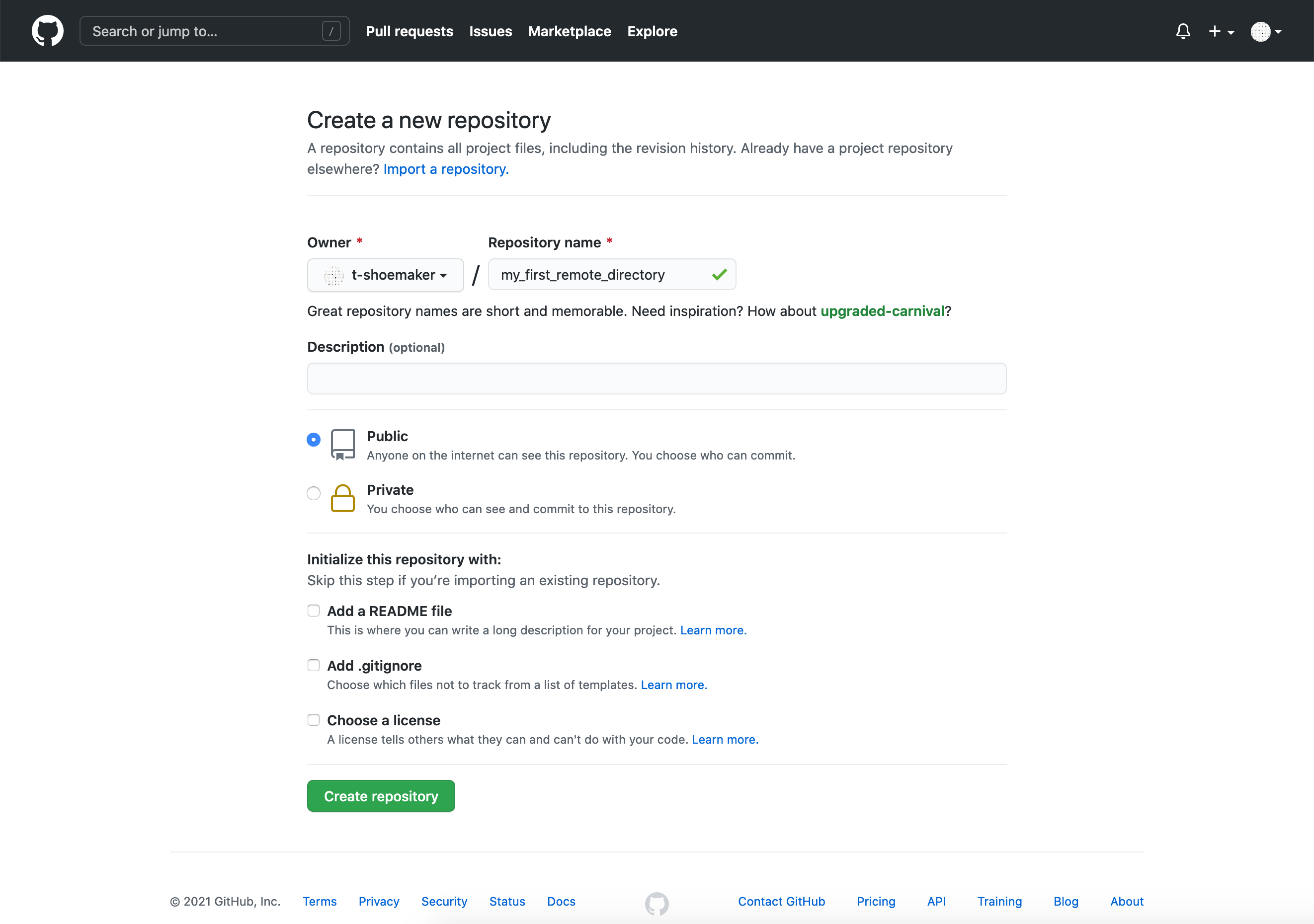

Because we’re initializing this repository from an existing directory, we won’t

bother with most of the extra details. But we do need a title, which should be

the same as what’s on your local computer (my_first_remote_directory). A

description is helpful but not necessary for our purposes; the same goes for a

license. Finally, we will choose to make this a public repository (meaning

anyone can see it).

4.3 Pushing a Local Repository

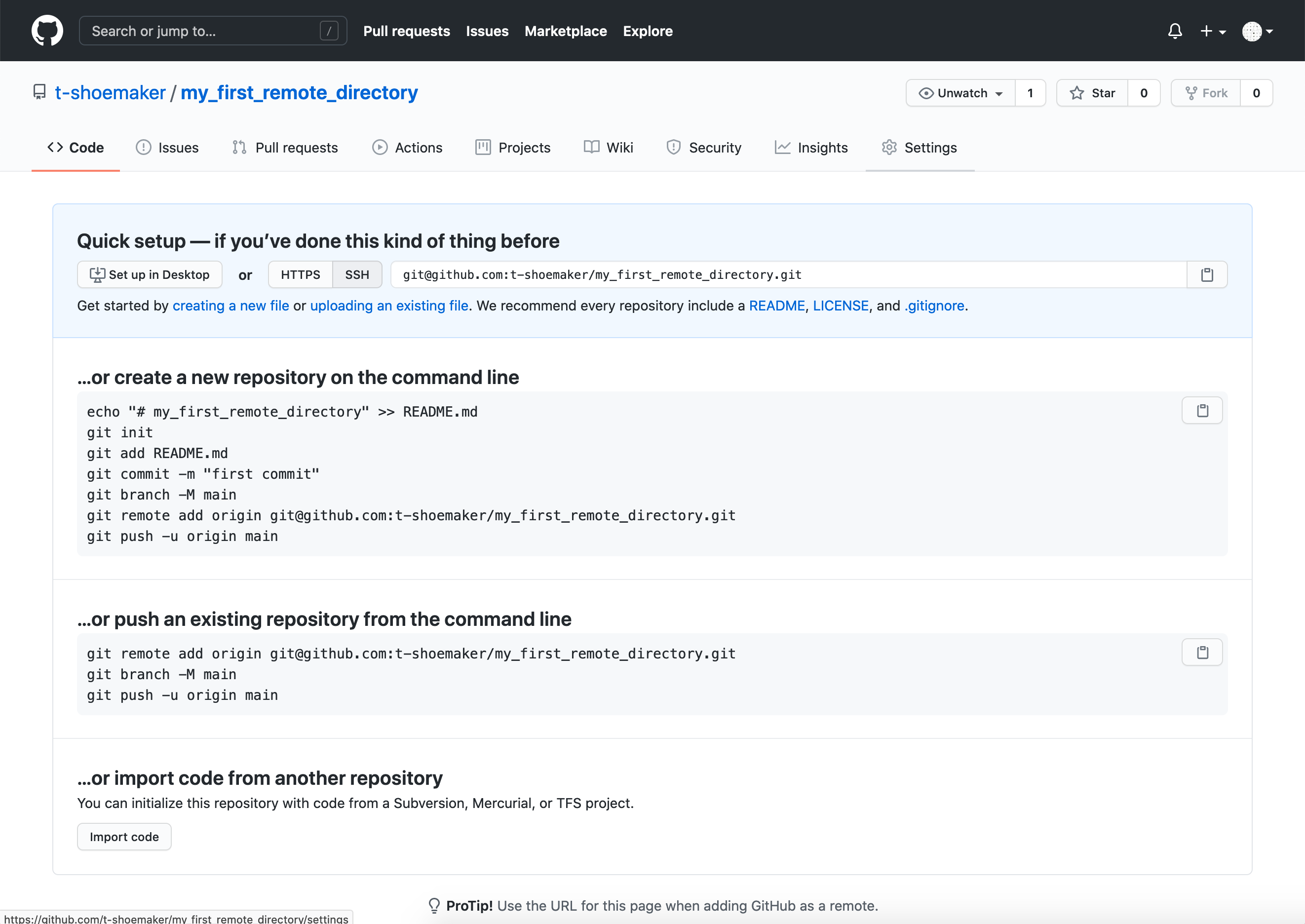

Once you’ve entered the above information, click “Create repository.” GitHub will take you to a new screen, which gives you a number of options for making or uploading new files to the repository.

Since we already have a repository made, we need to use the “Push an existing repository from the command line.” Pushing our repository is as easy as sequentially entering into the command line the three commands GitHub provides.

$ git remote add origin git@github.com:<your username>/my_first_remote_directory.git

$ git branch -M main

$ git push -u origin

Enumerating objects: 3, done.

Counting objects: 100% (3/3), done.

Writing objects: 100% (3/3), 239 bytes | 239.00 KiB/s, done.

Total 3 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0), pack-reused 0

To github.com:<your username>/my_first_remote_directory.git

* [new branch] main -> main

Branch 'main' set up to track remote branch 'main' from 'origin'.To summarize the above, we’ve done the following:

- Associated GitHub’s remote repository with our local repository (

git remoteetc.) - Made a new branch in our local repository called “main” (

git branch -M main) - Pushed the contents of main (from

origin) to a new, corresponding remote branch on GitHub

From here on out, when you want to update the remote repository with further

changes, you can simply use the shorthand git push after the usual save, add,

commit steps. Importantly, Git will only update the branch you’re on when you

enter git push, so before making any pushes, it’s a good idea to run a quick

git status command to make sure you’re on the branch you want to be on.

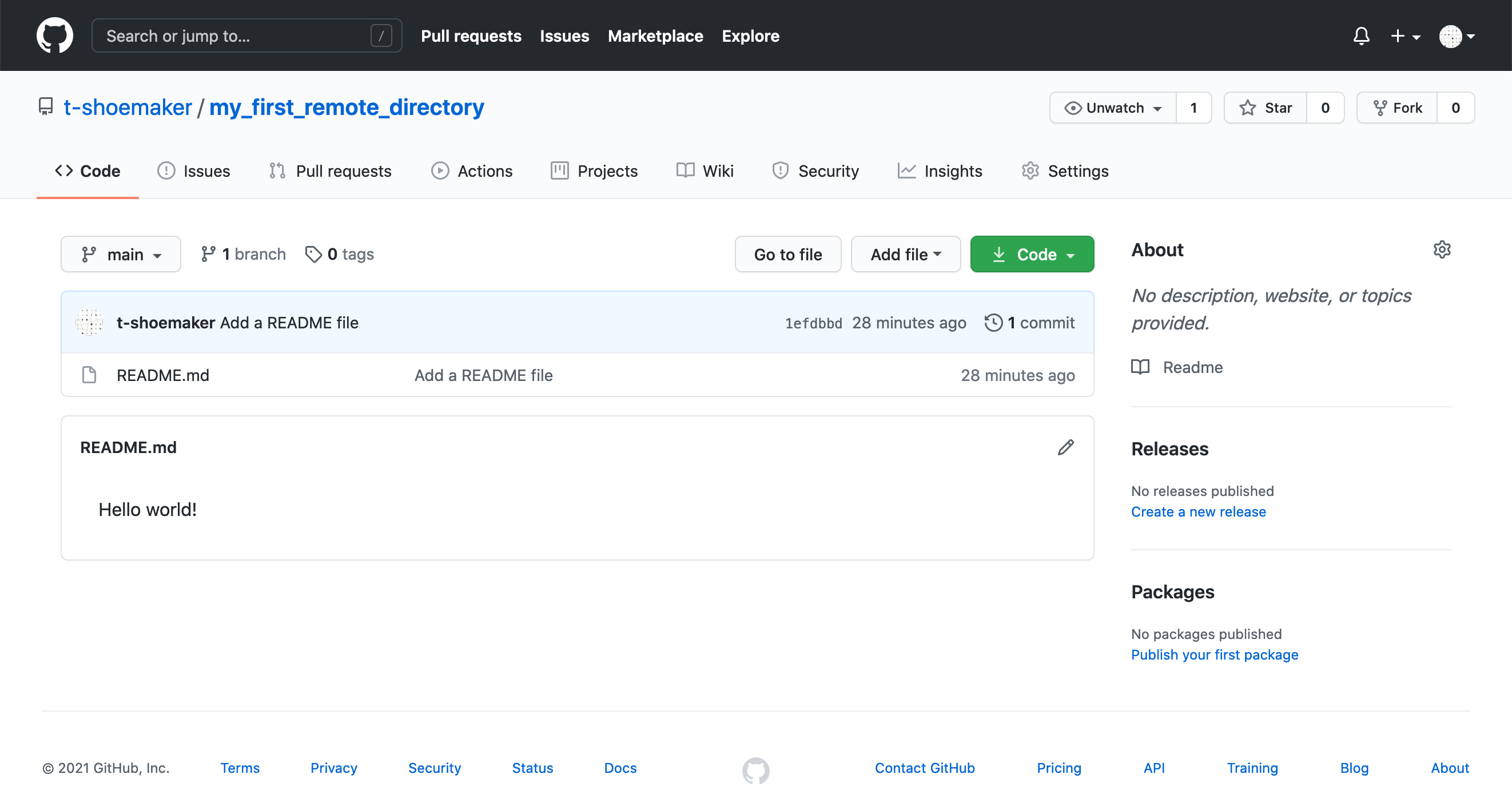

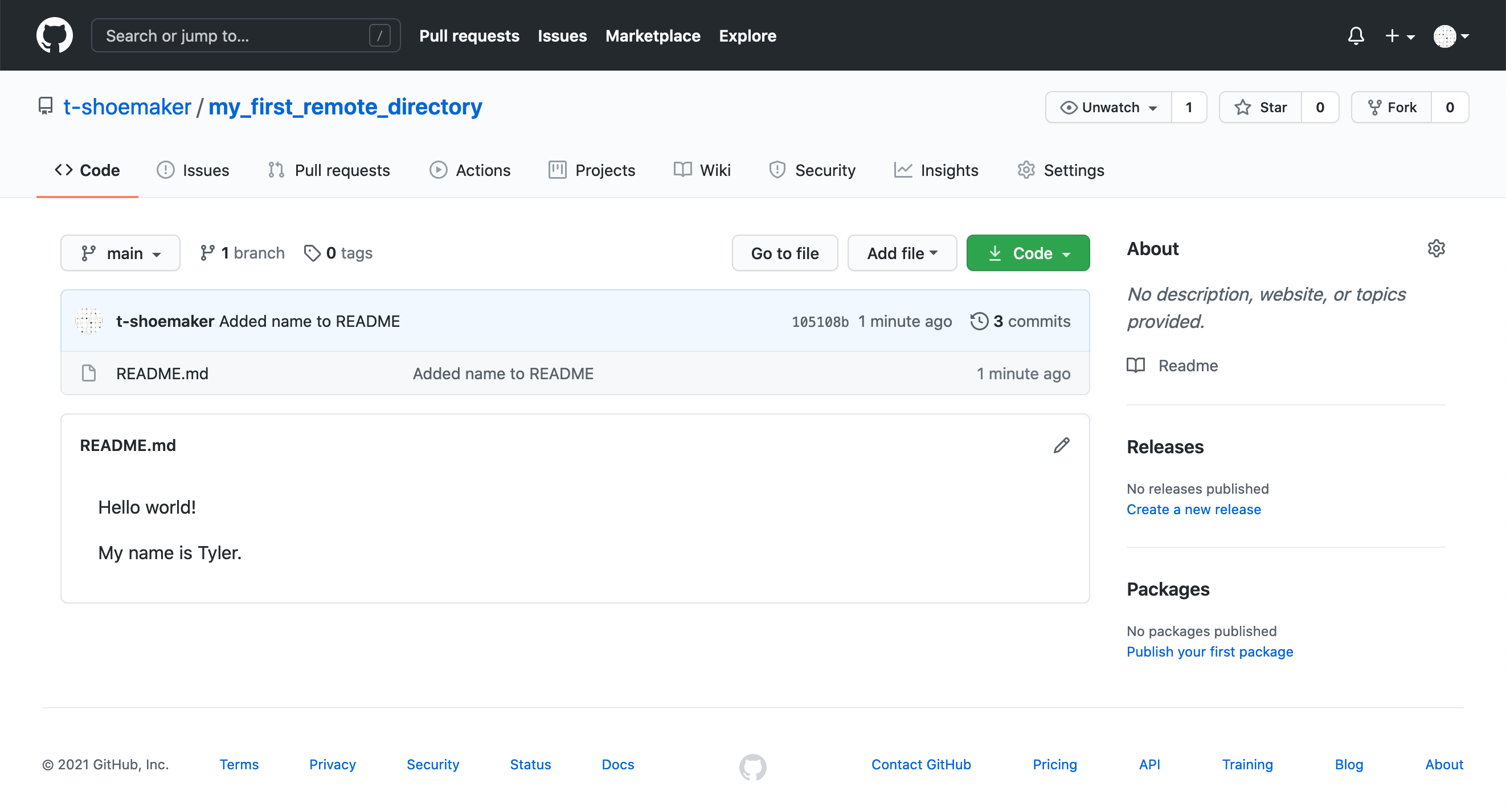

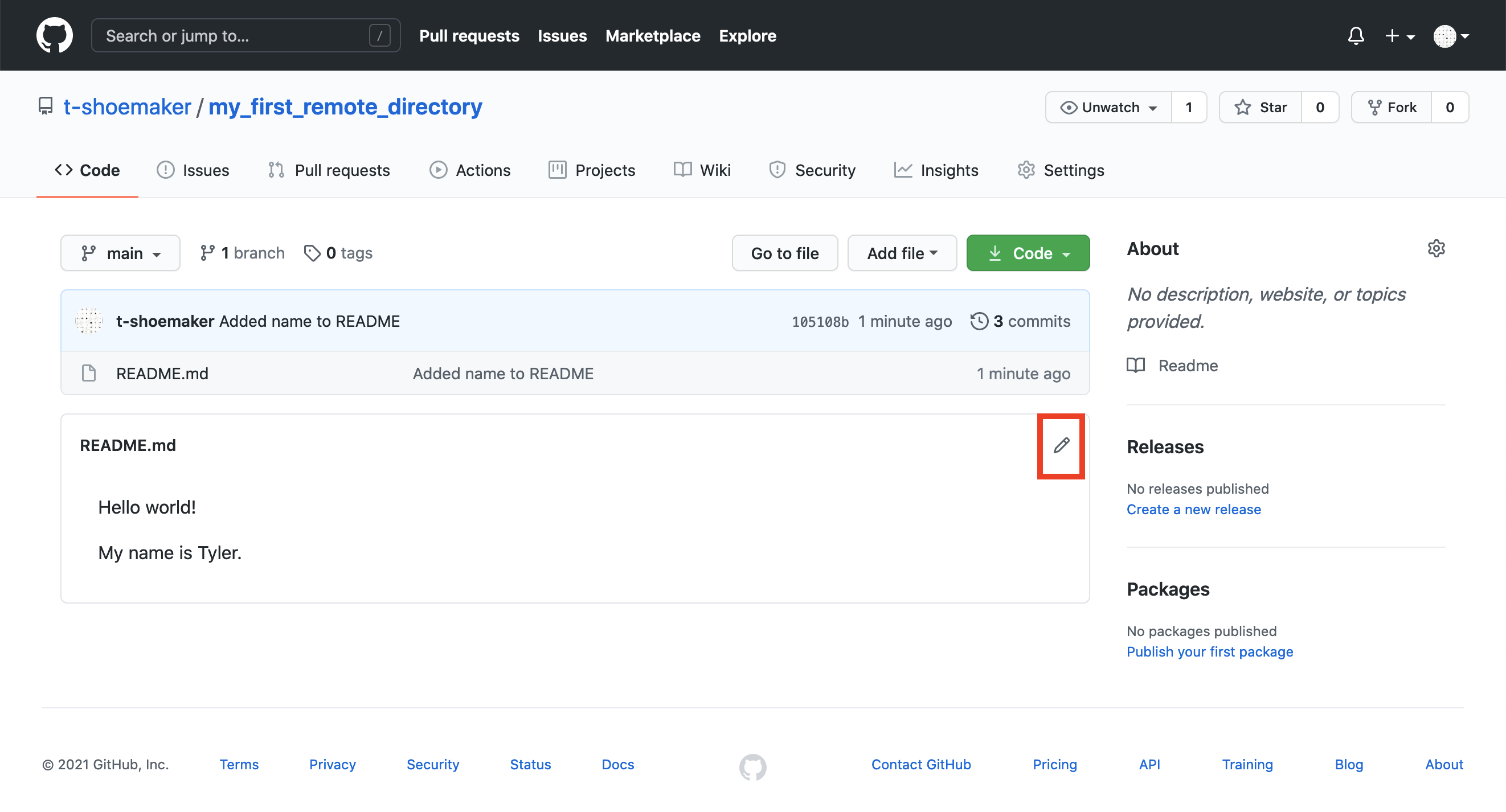

When you make your changes, the GitHub site won’t immediately refresh itself,

but if you click on the “Code” tab or on the name of the directory, you’ll see

that the repository has been synced and your README.md file is now online.

Note that GitHub automatically looks for a README file in your repository. If it finds one that contains renderable markdown code, it will render the file on your repository’s main page. (More information about writing effective README files is available through the DataLab’s data documentation workshop.)

4.4 Tracking Files Remotely

With this repository made, GitHub can start tracking changes you make to your files, much as Git does locally. The process works exactly like the one you do for Git, though it requires one more step.

First, we’ll alter our README.md. Reopen the file with Vim, skip a line down

from the line you’ve already written, and add “My name is

Your file should look like the following:

$ cat README.md

Hello world!

My name is <your name>.Then, add the file and commit your changes.

$ git add README.md

$ git commit -m 'Added my name to README'

[main 78bf509] Added my name to README

1 file changed, 2 insertions(+)If you want to push these changes to your remote repository, simply enter git push. Just as when you first linked your local repository to GitHub, you’ll

see a message appear about enumerating, counting, and writing objects.

$ git push

Enumerating objects: 5, done.

Counting objects: 100% (5/5), done.

Writing objects: 100% (3/3), 292 bytes | 292.00 KiB/s, done.

Total 3 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0), pack-reused 0

To github.com:<your username>/my_first_remote_directory.git

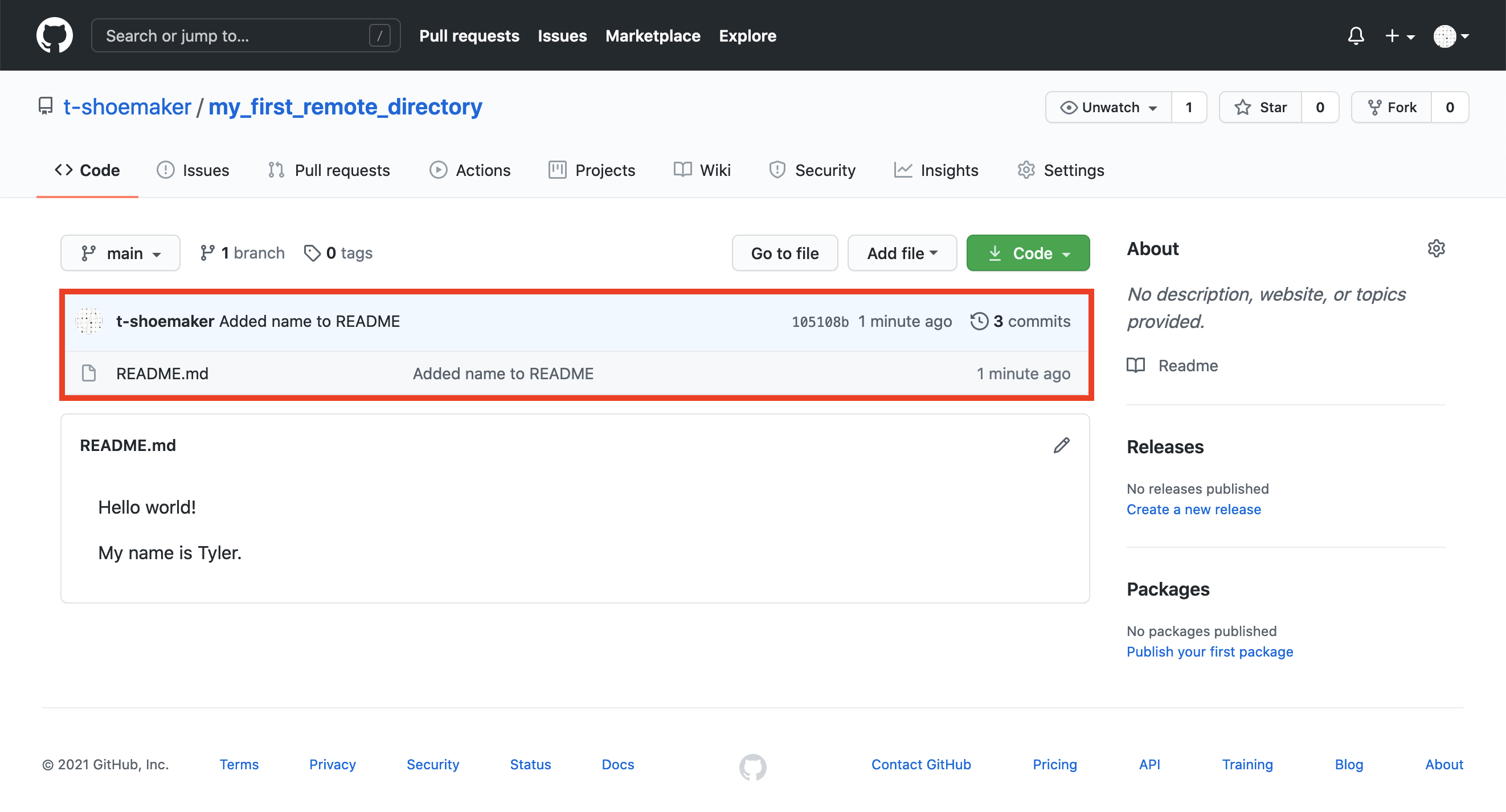

cad7867..78bf509 main -> mainAfterwards, if you refresh your file’s page on GitHub, you should see your changes:

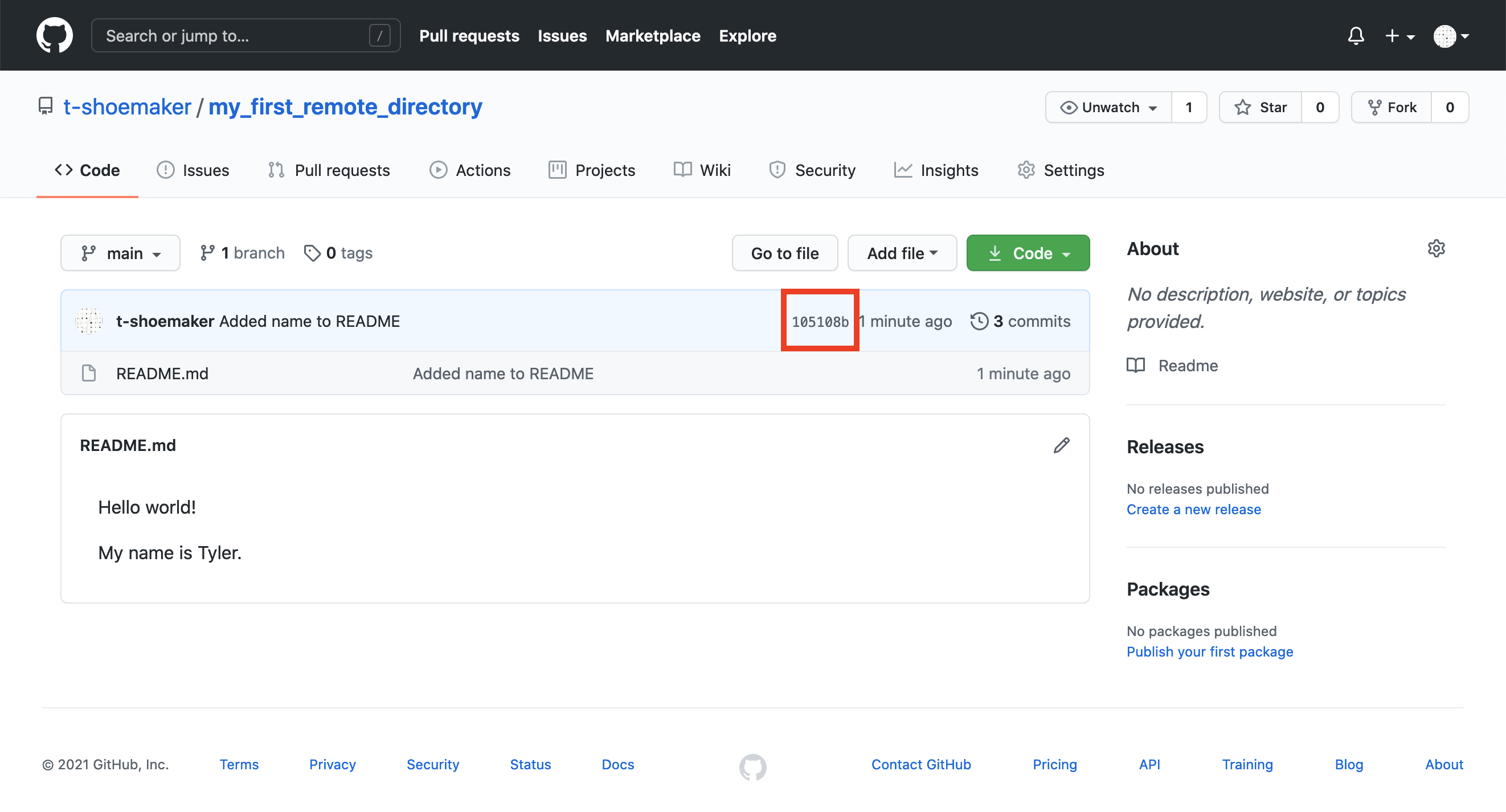

Note that your commit message appears here as well:

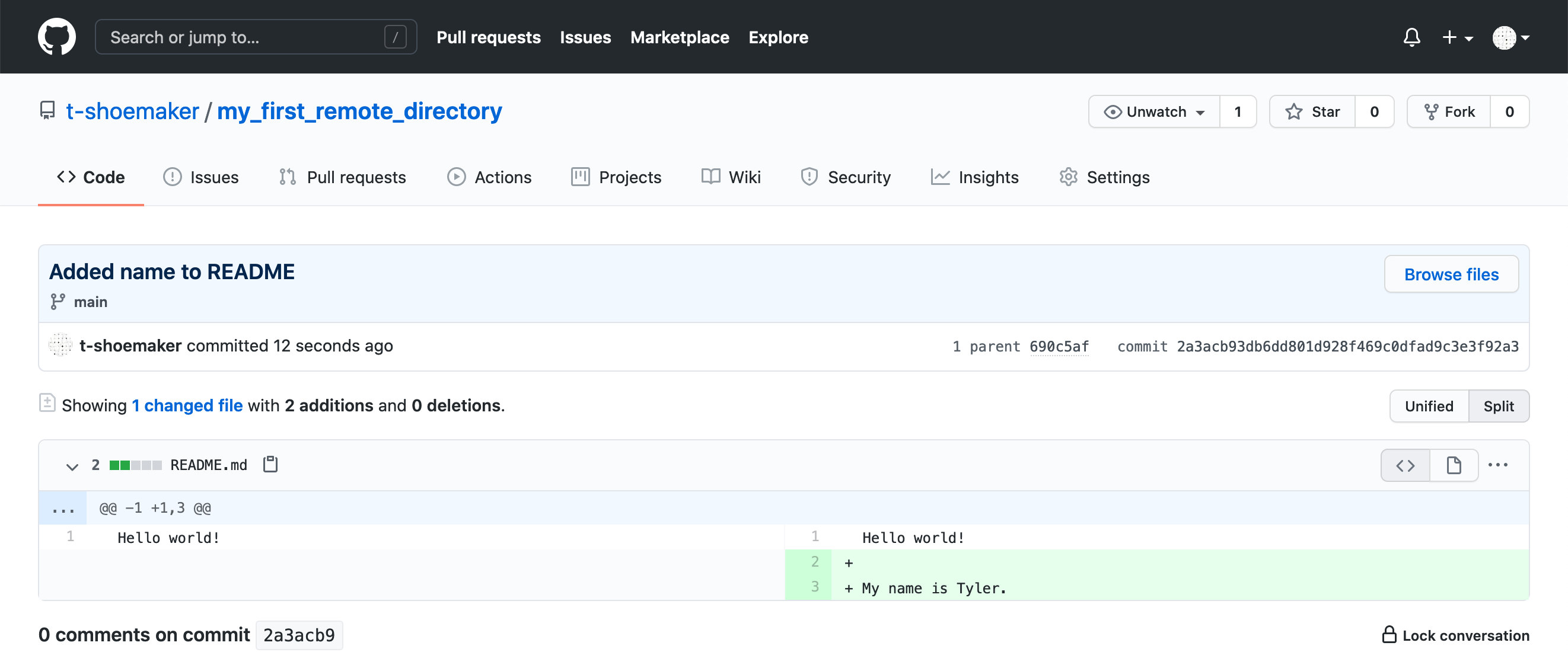

If you click the commit tag:

You’ll be taken to another page, which shows you the differences between your

old version and the new one. This is like running git diff <commit a> <commit b> on your local computer.

4.5 Pulling Changes from a Remote Directory

Before moving on, it’s also worth noting that we can pull changes directly from GitHub. If a file has been altered on the remote version of a project, GitHub offers functionality for syncing that file with your local copy (or creating a new file altogether, if need be).

For example, if you return to the main page of “my_first_remote_directory”, you can alter the README directly on GitHub. Click the pencil in the right-hand corner of the rendered file.

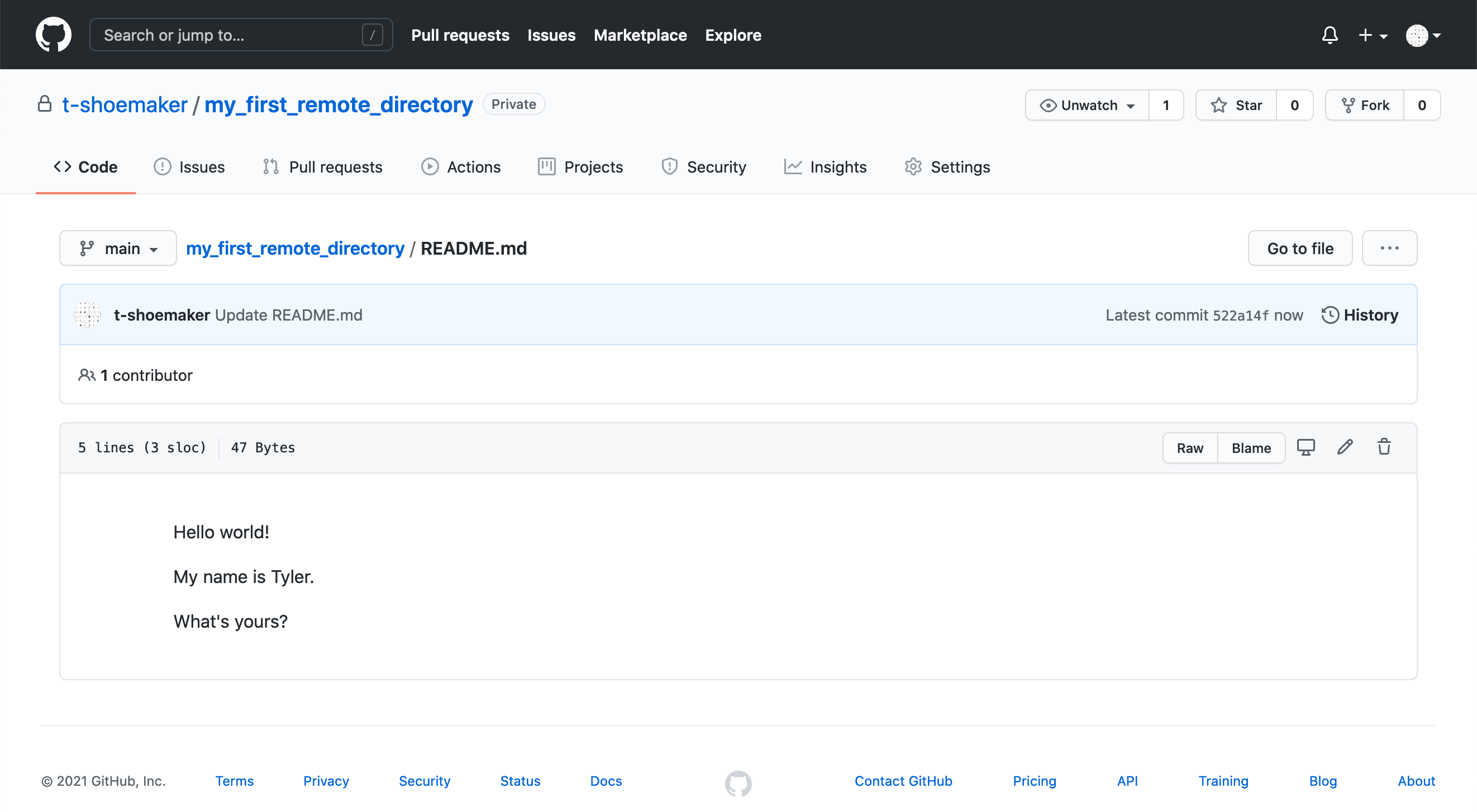

This will open up a text editor interface. Using it, add “What’s yours?” on the fifth line of the document. The complete document should look like this:

Hello world!

My name is <your name>

What's yours?Scroll to the bottom and click the green “Commit changes” button. This is the

equivalent of doing git add <file> and git commit -m <message> on the

command line.

You’ll see something like the following:

Back on the command line, you can run git fetch to see whether any changes

have been made to the remote repository.

$ git fetch

remote: Enumerating objects: 5, done.

remote: Counting objects: 100% (5/5), done.

remote: Total 3 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0), pack-reused 0

Unpacking objects: 100% (3/3), 666 bytes | 333.00 KiB/s, done.

From github.com:t-shoemaker/my_first_remote_directory

78bf509..2335530 main -> origin/mainWith this information about your remote repository pulled down to your computer, you can run a status check. If you do so, you’ll see that your local repository is now out of sync with the remote one.

$ git status

On branch main

Your branch is behind 'origin/main' by 1 commit, and can be fast-forwarded.

(use "git pull" to update your local branch)

nothing to commit, working tree cleanIf you haven’t made any changes to your directory, syncing it with the remote

version can be achieved with a straightforward pull command:

$ git pull

Updating 78bf509..2335530

Fast-forward

README.md | 2 ++

1 file changed, 2 insertions(+)Your files are now synced. A later portion of this reader will discuss how to handle this process when you have made changes to your directory between the time the remote was altered and the time you go to make a pull.

4.6 Keeping Certain Files Untracked

Before moving on, let’s briefly consider files that you don’t want Git/GitHub to track. When you’re using remote repositories, you’ll often find yourself in situations where you don’t want to share certain things with everyone who might come across your repository. Information about your system configuration, passwords, or other sensitive data are all examples of things you shouldn’t push to GitHub. Most modern operating systems (such as Mac or Windows) also automatically create and store a lot of hidden configuration files within the computer’s directory structure. For example, below is a file listing for a directory containing resources for a workshop the DataLab offers about text mining and R:

$ ls

D3VIS data gephi_tutorial kumu_tutorial r_networks readme.txt scraping text_miningAnd here is the same directory listing showing hidden files:

$ ls -a

. .DS_Store D3VIS gephi_tutorial r_networks scraping

.. .git data kumu_tutorial readme.txt text_miningNote the appearance of the previously hidden .DS_Store and .git directories

when we run ls -a. These are those system- and directory-specific

configuration files. Git is pretty smart, and it knows to ignore its own hidden

configuration files, but we need to tell it explicitly to ignore the other one

using a special file called .gitignore. You can create a .gitignore file

from scratch using Vim by typing vim .gitignore on the command line. When you

do this, Vim will open a new file. Then, you simply add the names of files and

directories that you want Git to ignore, putting one per line of the new file.

.httr-oauth

.DS_Store

.config

data/*Note in this example that we’ve also added the data folder and any of its

contents to .gitignore. This is for two reasons, which we discussed earlier:

1) it’s generally bad practice to track data files with version control

systems; 2) the free version of GitHub (which you’re probably using) puts a cap

on the total size of a repository. It would be a waste of space to have data

eating away at that size limit.

Generally speaking, you should place your .gitignore file in the root of your

repository, where it will control Git behavior for the repository. You can

create a global .gitignore file, but this requires you to run various system

configurations on Git itself. Information on this process can be found

here. GitHub also provides a nice

repository of template .gitignore files for various types of development

here.